It is not the Commodore 64's longevity, an incredible 13-year run from the first unit sold to the last one produced, that should have finally settled the oddly enduring playground arguments of the '80s on which was the superior 8-bit machine. Nor is it the model's popularity, recognized by the Guinness Book of World Records as the highest-selling home computer of all time (though the exact numbers vary wildly depending on who's counting).

These are mere side discussions, ignoring the real reason why this age-old debate should have been put to rest a long time ago: namely, the breathtaking range of the Commie's software library. Enormously expansive (spanning across several thousand commercially released titles), stupendously varied (from profound meditations on the meaning of life in Activision's early experimental effort, Alter Ego, to unlikely adaptations of radio soap operas in Level 9's The Archers), and, at times, staggeringly ambitious (Project Firestart, gaming's first true survival horror and a title that's basically Dead Space without the fancy 3D visuals, was squeezed inside a couple of 170kb floppies), no other computer of that era could offer a comparable breadth of experiences. The question on which the newly-released Mini hinges, for me at least, is whether it can possibly capture the spirit of that legendary machine in its rather limited selection of 64 titles.

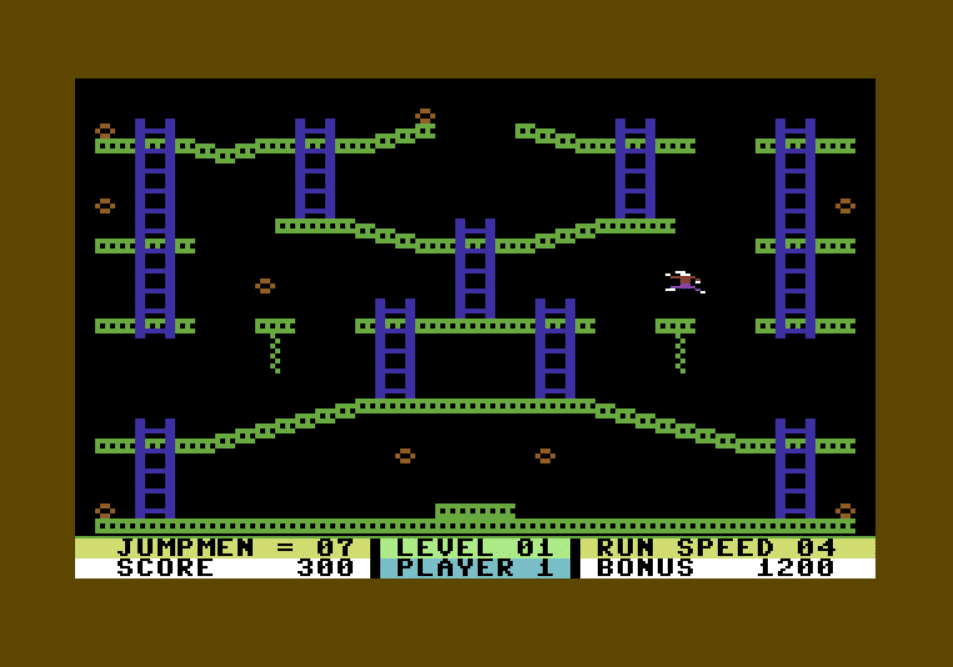

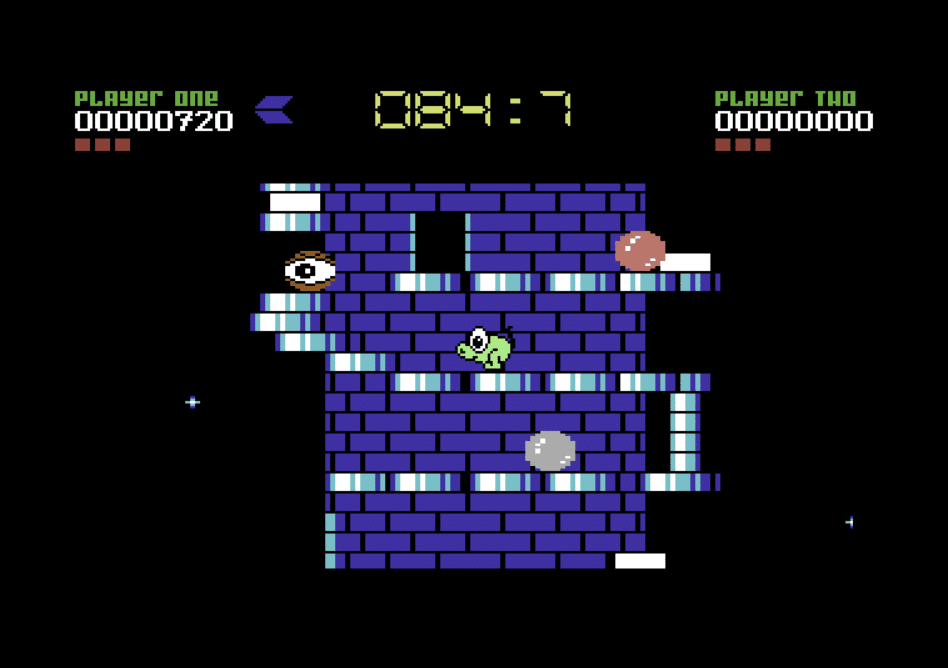

The selection is admirably diverse, reading almost like a geologic column of C64's history. The earliest game in the Mini library, Jumpman by American software house Epyx, was released in 1983 when Commodore's flagship computer was barely a year old and copyright law an even blurrier concept within the industry than it is today. Inspired (to put it charitably) by Donkey Kong, Randy Glover's platformer nevertheless featured a number of original ideas, such as the homing missiles roaming around each screen necessitating constant movement, and the fireman poles strewn around most stages that would complicate your anxious itinerary with a forced descent (not unlike a real-time version of snakes and ladders).

The latest in the lineup is Nobby the Aardvark, a deceptively cute, multi-scrolling action adventure released in 1993, one year before the Commie was discontinued. Seen side by side, it's hard to believe the two titles belong in the same hardware generation, an illuminating account of how developers' growing familiarity with the platform enabled them to squeeze the potential out of its limited technical capacities to create increasingly impressive works.

Publishers are less evenly represented, with a heavy focus on UK-based companies: in particular Hewson, Gremlin, and Thalamus account for roughly half the titles in the collection. The latter especially is fondly remembered by fans for its special relationship with the C64, a modern equivalent might be Naughty Dog and Sony, and developed a series of visually spectacular, mostly exclusive (and, occasionally, slightly overrated) titles that would often provide the last line of defense in comparisons with the Amstrad and Speccy. American software house Epyx also contributes several titles, mostly the multi-event sports simulations it became famous for (including the best of the bunch, World Games). A few stray releases from less prolific publishers (Odin, First Star, Electric Dreams) round off the Mini's lineup.

Some of the era's most typical genres are unsurprisingly absent. The C64 Mini lacks a fully functional keyboard, so it would be impossible to type the commands required for a text adventure or an RPG - although the latter category makes an appearance via the rather archaic but historically significant Temple of Apshai Trilogy of overhead dungeon crawlers.

Otherwise, there's a fairly exemplary range of the era's most popular genres: arcade adventures (Hawkeye, Robin of the Woods), puzzle games (Deflektor, Chip's Challenge), platformers (the Monty Mole series), even a couple of the more accomplished racing games the C64 was traditionally struggling to produce (Pitstop II and Super Cycle).

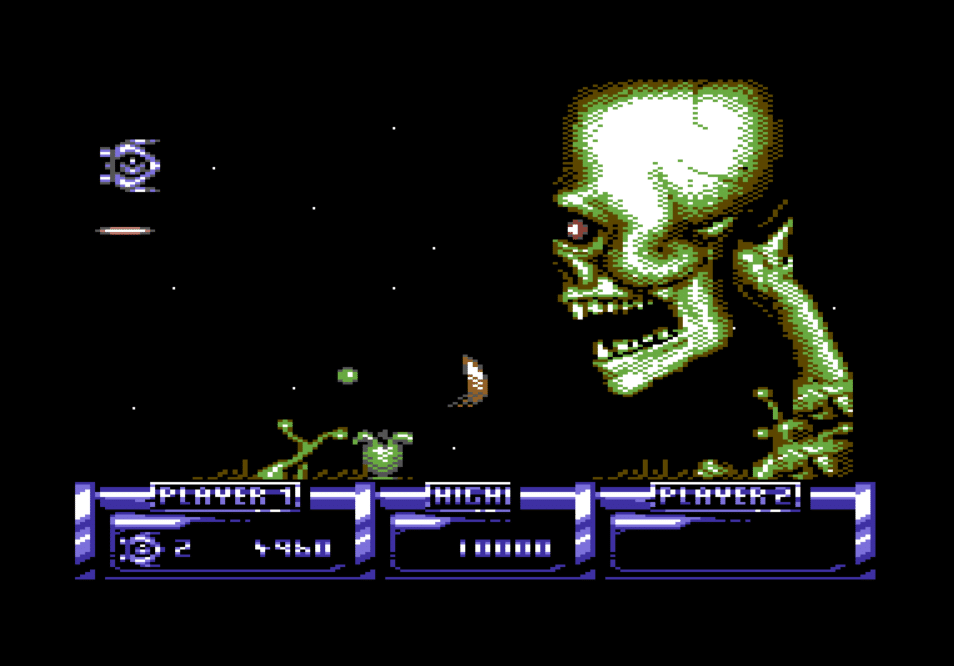

Most importantly, there are several noteworthy examples of the genre typically associated with the platform and one its hardware was uniquely configured to handle: the side-scrolling shooter. Perennial reference point for nostalgic fans, Armalyte, is naturally included but it's a game that has aged poorly: its visual flair no longer capable of concealing the sluggish pace, uninspired enemy design, and iffy collision detection. Moreover, its primary source of appeal, the option for simultaneous cooperative play (still a rare affordance in the late '80s) will be of little use to the average Mini user, since the machine does not come with a second controller.

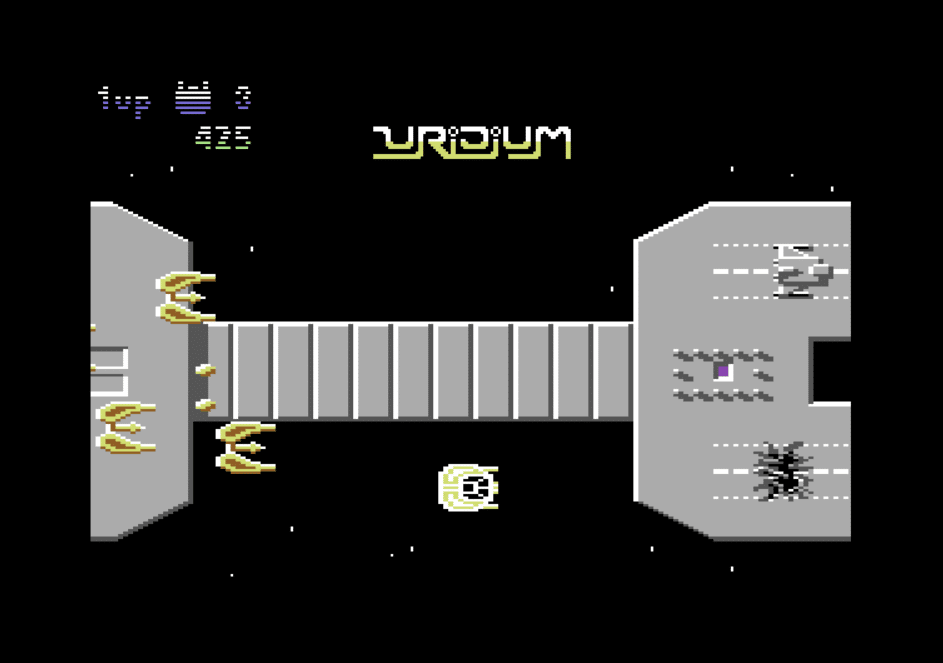

On the other end of the quality spectrum lies Andrew Braybrook's Uridium. Silky smooth animation unrolling at an unfaltering 50 frames per second, deadly enemy waves coming at you from both sides of the screen, and, most importantly, an original, wonderfully visceral control method that allows you to roll and pitch at different speeds, weaving through enemy formations and ground-based obstacles to reach the landing platform at the end of each stage, Uridium can be legitimately considered one of the best shoot 'em ups of its era and is one of the real highlights of the Mini's library.

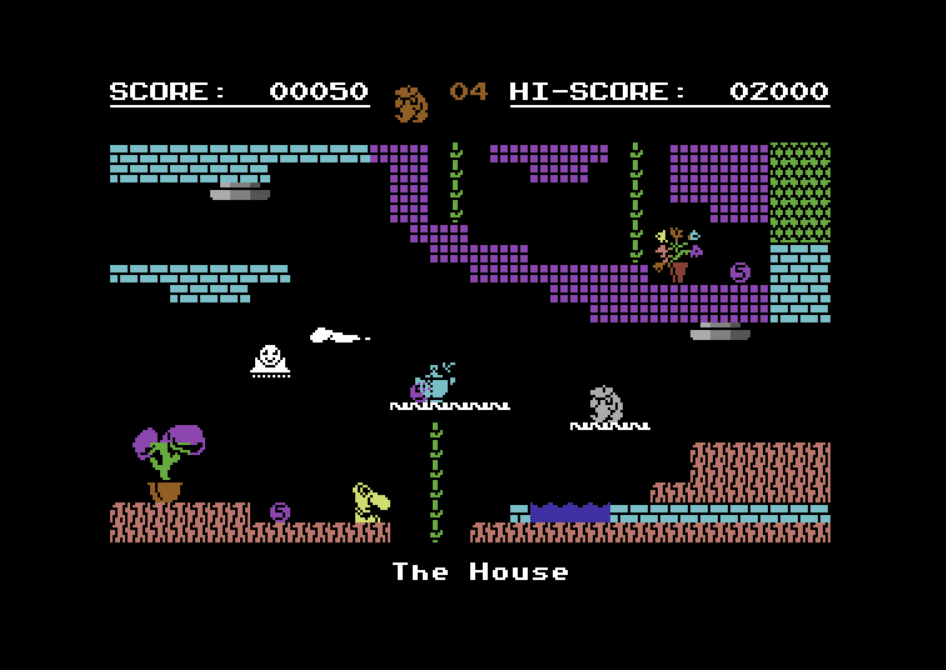

However, it is another shooter included in the package, Firebird's IO, that offers a fascinating glimpse into a set of game design principles that has changed drastically in the intervening decades. Lauded at the time for its gorgeous graphics, especially the bright metallic colors and impressive end-of-level bosses, IO's difficulty will come as an absolute shock to anybody with more contemporary sensibilities, even those weaned on hardcore platformers like Super Meat Boy and N+. Speed, deadly, cramped scenery, and unpredictable attack patterns make it almost impossible to survive any single wave of enemies unless you are both familiar with their flight behavior, fast enough to adjust your position to avoid them, and precise enough not to crash into the backgrounds.

These were principles borrowed from the arcades, where difficulty was a necessary requirement to keep players feeding the coin slot. While home computers weren't hungry for your quarters, their limited memory meant that difficulty had to compensate for their meagre content. A full playthrough of IO by someone who has mastered it takes less than 15 minutes, but it takes several hours just to learn how to survive the first level. The fact that most action games of the 8-bit era were designed for short bursts of play presents an interesting question regarding contemporary users and the Mini. Such titles are great for a quick fix, a palate cleanser after those interminable open world slogs, but is there anywhere in its library the possibility of a longer-term relationship?

Impossible Mission 2 is a typically unforgiving action adventure, but at least reins in the original's off-putting difficulty and is generous enough with its lives to allow the possibility of hour-long sessions and a genuine sense of progress while exploring its high-tech towers, decoding hidden messages, and somersaulting over robotic guards.

Similarly Speedball 2, a futuristic, fully-armored version of American football where you earn extra points for having your opponents carried out of the arena on a stretcher, is made for extended, multi-session engagement. One of the first titles to apply the now ubiquitous RPG framework on a sports game, not only did individual teams in its league behave differently (old-time players will still recoil in horror every time the name Super Nashwan is brought up), but you could also spend the credits earned with each match for a new signing which usually came not just with improved skills but also the added bonus of a unique look: scars, piercings, and tattoos, to replace the square-jawed, vacantly staring Aryan faces of your original team. While not as polished as the classic Amiga version this is still a joy to play, both the moment-to-moment engagement and the longer term progression in the league, and is a perfect fit for the Mini's built-in save option.

An aspect of the C64's timeless appeal that could not have gone unaddressed is SID, its much coveted sound chip. Visual superiority in the 8-bit world was a subjective and ever-debatable thing: Amstrad could dip into a broader range of colors and Spectrum fans could always point to Commodore's inferior handling of 3D, but neither of those computers still have club nights organized around their game soundtracks alone, nor did they spawn a worldwide hit based on a sample from an obscure title, more than a decade after its release.

Commodore's composers were as close to superstars as the oft-overlooked profession has ever managed in the industry, and several of those most fondly remembered are present in the Mini's collection. Ben Daglish, conjures up some medieval synths for Firelord, Martin Walker's ominous drones and metallic chirps slowly build to an anxious crescendo in Snare, and Rob Hubbard accompanies Mega-Apocalypse's frantic action with a techno tune so immediately catchy that it almost compensates for the game's visual blandness.

Finally there's a fair share of genuine oddities: the types of games making the C64, as well as the other home computers of the 8-bit era, such distinct platforms in the history of the medium: those innovative, unusual, or just plain weird ideas that were less likely to be greenlit in the tightly controlled environments of console and arcade publishing. Trailblazer's unique take on the racing genre, saw you hurtling towards the finish line with a ball whose behavior would change depending on the color of the square it had last touched, an exhilarating, almost hypnotic experience.

Skool Daze simulated a full day in a strict boarding school, included all the stereotypical characters associated with the setting, and shrewdly allowed you to change their names so you could insert your own teachers and schoolmates. And in the brilliant Nebulus, you're ascending a cylindrical tower that turns as you move, throwing new hazards your way with every revolution.

These were worlds whose rules were yet to become familiar, filled with the kind of inspiration which always accompanies the first burst of popularity in a new medium before conventions calcify into a specific idea of what it can and cannot do. The Mini lineup, even in its occasional filler titles, not only provides an intriguing peek into a bygone age of gaming that is inherently engrossing in its otherness: it also includes a handful of games that are as delightful to play now as they were three decades ago.

If you weren't there, it may not mean much. But if you have any fondness for the Commodore 64, then the Mini conjures that era when 16 colors and a 320x200 resolution was the cutting edge of technology — and creativity knew not our contemporary bounds.