Videogames have long heeded the call of the sea. Its unboundedness promises freedom and the thrill of adventures, as well as offering a blank canvas for pirates, explorers, and treasure hunters in games like Pirates!, Salt, or Assassin’s Creed: Black Flag. The folksy Burly Men at Sea invites us into humorous interpretations of sailors’ fairy tales, or what happens on the surface, while a game like Abzu is all about the ecstasy of swimming through schools of colorful sea creatures. Even the adventures of landlubbers, like The Witcher 3, find it hard to resist the taste of salt, setting us up to go a-sailing and a-whale watching.

Very rarely, games hint at the ocean’s darker depths. The claustrophobic underwater horrors of Soma or Bioshock dive into the unfathomed depths of the human consciousness and political anarchy respectively. Both The Sailor’s Dream and Abzu deal with tragedies; a lost sailor in the former, species extinction in the latter.

One particularly influential tradition, however, has barely left its mark on games. It’s a sublime vision of the ocean that sees overwhelming beauty and terror inextricably interlaced in its depths, that is intimidated yet fatally attracted by the humbling grandeur of the sea: a place eternally unknowable, and indifferent to the fortunes of the seafarers it both sustains and destroys, swallowing them body and soul. It’s a tradition exemplified by Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby Dick, the rambling account of mad captain Ahab’s ill-fated attempts to take revenge on the eponymous albino sperm whale. Here, whales and other creatures of the deep appear like primordial, pagan gods of a wet wasteland whose arcane depths cannot be measured in fathoms alone, since they are metaphysical, even mystical:

“But lulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie is this absent-minded youth by the blending cadence of waves with thoughts, that at last he loses his identity; takes the mystic ocean at his feet for the visible image of that deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading mankind and nature; and every strange, half-seen, gliding, beautiful thing that eludes him; every dimly-discovered, uprising fin of some undiscernible form, seems to him the embodiment of those elusive thoughts that only people the soul by continually flitting through it.”

Moby Dick is a delirious novel, veering into the fantastical, but it is firmly anchored in actual historical events. There are accounts of a real albino whale called Mocha Dick who was allegedly victorious in more than a hundred ‘battles’ against whalers. In 1820, a sperm whale attacked and sank the Nantucketer whaleship Essex, whose crew drifted in boats through the Pacific Ocean for months. When the few survivors were discovered, they were sucking the bone marrow from what remained of their fellow sailors (see In the Heart of the Sea by Nathaniel Philbrick). When the whaling ship Ann Alexander was rammed and sunk by a sperm whale shortly before the publication of Moby Dick, Melville wrote: “Ye Gods! What a commentator is this Ann Alexander whale. What he has to say is short & pithy & very much to the point. I wonder if my evil art has raised this monster.” In the 19th and well into the 20th century, the ocean still inspired awe, terror — and stories half real, half submerged in fancy.

Games rarely tap into this bulging barrel of whale oil to fuel their forays into the blue. Perhaps it has to do with how games, obsessed as they are with player agency, are uncomfortable with exposing their players to an unknowable, capricious force that is so much bigger than they. Or perhaps the ever-present threats of ecological degradation make the oceans seem more deserving of pity than soul-annihilating awe. The vastness of the sea that contained immeasurable multitudes shrank, in our minds, to a shadow during the last century or so: mastered by modern fleets; packaged-up and explained in documentaries; something we now journey across in days or weeks rather than months and years.

In this context it's important to remember the suffocating, inspiring power the ocean once had over our collective imagination. In a deluge of videogames, this imagination surfaces here and there like a fluke and a spout before vanishing again.

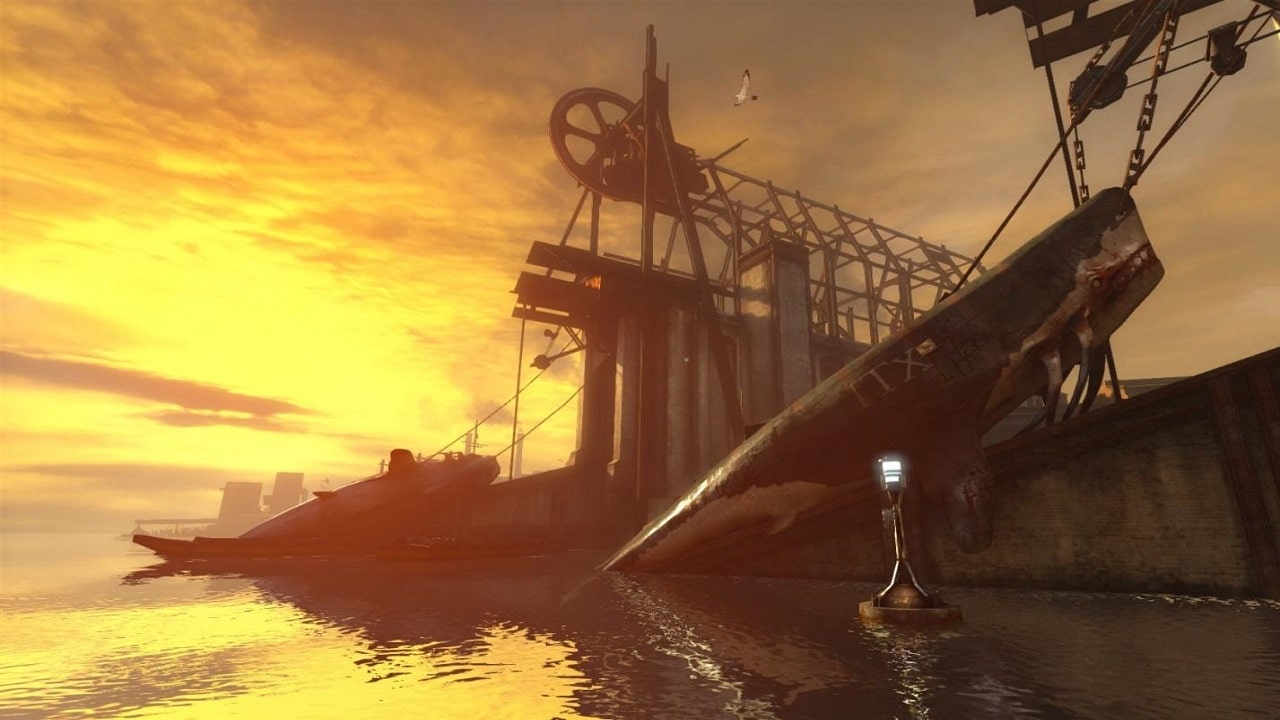

In Arkane’s Dishonored games the ocean is in the periphery, but always lurking in the background. Dunwall is the capital of a maritime empire, and the ocean's importance is reflected in painstaking detail through the culture and industry of the city. Whales both real and imaginary are omnipresent, making appearances in meat adverts, as masks and decadent statues in the homes of the well-to-do, and in books full of sailors’ old yarns. They’re hunted and processed for the oil which fuels the empire’s industrial revolution.

They also have a darker, dare I say arcane, aspect: whales, of all the animals in Dishonored’s bestiary, are the ones most associated with witchcraft, the occult, and otherworldly realms. Whale scrimshaw (carved bones covered in runes) unlock magic powers and whisper to the player. The mutilated body of a whale towers over Granny Rags’ lair in the sewers, overshadowing her sinister rituals. In Dishonored 2, a whale drifts past you through the Void, seemingly the only living creature in this otherworld apart from you and the Outsider. Their song, too, has a special significance. In a letter called “Answer from Wyman”, we read of a terrible omen: whales “singing their songs in reverse.” And according to 'Bonecharms', runes carved from whale bone are somewhat special, as they “sing in the night.” Dishonored never tries to explain away the whales’ arcane significance, wisely leaving the mystery intact. Like the hieroglyphs left behind by ancient civilizations, Melville wrote, “the mystic-marked whale remains undecipherable.”

Bloodborne, too, hints at hidden depths beneath the water’s surface. In the last chapter of The Old Hunters DLC, the game sends the player on a journey towards the dark heart of a ruinous fishing hamlet. It’s a place of rotting timber and fishing nets, inhabited by molluscs and encrusted in barnacles. Its murderous fishmen, hunting the player with harpoons and weaponized anchors, are close kin to the inhabitants of Lovecraft’s The Shadow over Innsmouth but — thanks to From Software’s indebtedness to the aesthetics of the sublime — there’s more than a trace of the morbid grandeur found in Moby Dick.

The cliffs, caverns and masts of decaying ships on the horizon are nightmare visions with a touch of pathos. The most striking sight, and the focal point of the entire hamlet, is the pale and enormous cadaver of Kos stranded on the hamlet’s shore, first seen from high above. A passage from Moby Dick, describing the sighting of a giant squid, seems to sum up the impressions evoked by Kos:

“We now gazed at the most wondrous phenomenon which the secret seas have hitherto revealed to mankind. A vast pulpy mass, furlongs in length and breadth, of a glancing cream-color, lay floating on the water, innumerable long arms radiating from its center, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas, as if blindly to clutch at any hapless object within reach. No perceptible face or front did it have, no conceivable token of either sensation or instinct; but undulated there on the billows, an unearthly, formless, chance-like apparition of life.”

Who sunk those ships? How did Kos die? Bloodborne takes the answers to such questions to the bottom of the sea and doesn’t allow the player to follow them. Like an iceberg, what we see above the surface is only a fraction of what is there.

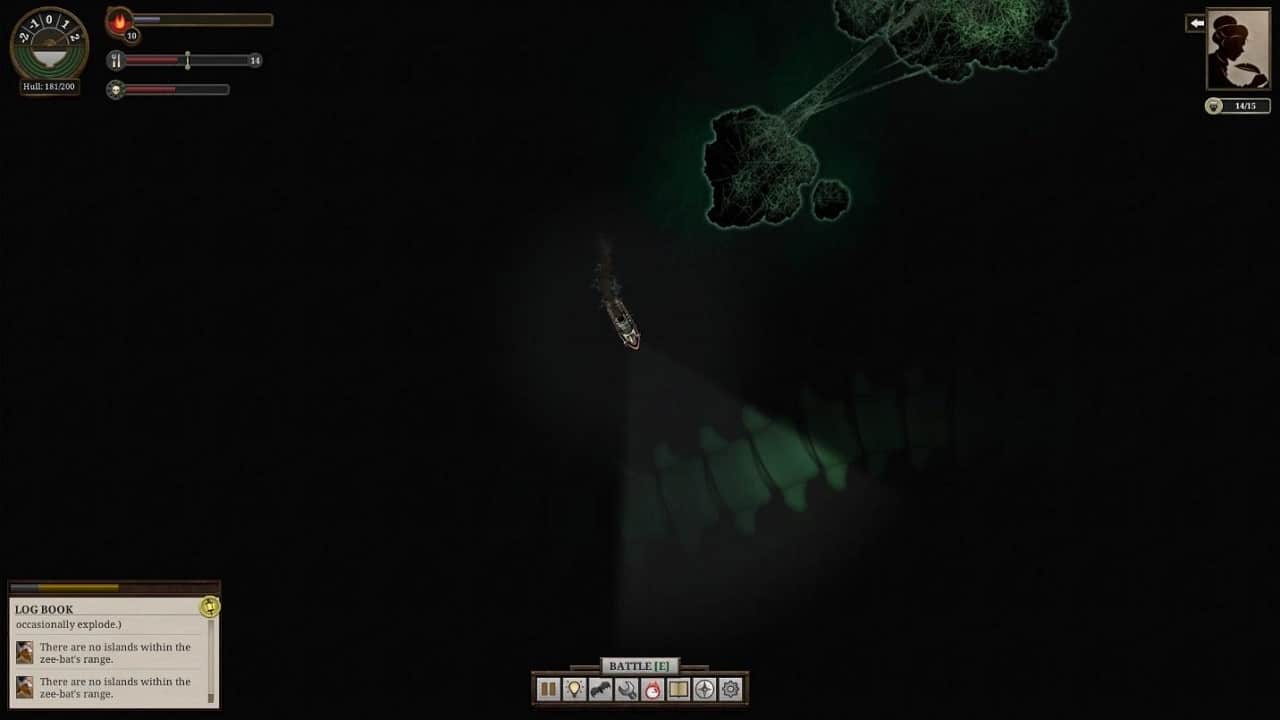

The ocean takes center stage in Failbetter Games’ Sunless Sea. As a ship’s captain in a vast, subterranean world, it is your mission to explore the islands and mysteries of the Unterzee. The game’s structure communicates some of the dangers and psychological pressures associated with long sea travels. Every journey starts in Fallen London and ends in Fallen London; a haven where you can trade, resupply and recover. Straying too far from home in pursuit of riches and discoveries can prove fatal; perhaps you anger some colossal sea creature, run out of fuel or rations, or your crew becomes mad with fear in the constant darkness and kills you in a mutiny. The threats of wreckage, cannibalism and madness are your hidden stowaways on these deceptively calm voyages.

As in Dishonored or Bloodborne, the sea is home to many mysteries. There are delirious nightmares that plague you and your crew, sea gods with ominous names like ‘Salt’, ‘Stone’ and ‘Storm’, and ancient, lost places that offer forbidden knowledge in exchange for a visitor’s soul and sanity. Venturing ever deeper into the Unterzee and nearly being swallowed by is an experience mirrored by the fate of Melville’s young sailor Pip, who falls out of a whaling boat:

“The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of water heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic.”

The fragmented insights gleaned from the ocean are too big for human minds to contain. It is no coincidence that the mysteries of Sunless Sea aren’t there to be solved, but simply to be seen, experienced and wondered at.

A stealth game, an action RPG, and a choose-your-own-adventure style exploration game: three titles that have little in common beyond Victorian settings influenced by the dark tales of Moby Dick and its ilk. Today the wonder of the ocean, in the popular mind, seems to be drained by ecological disasters and our technological mastery — but don't be fooled, we depend on the oceans as much as we ever did. Perhaps these stories may help us find fresh perspectives and respect, rather than pity, for the ocean and its creatures. And whether we see and feel it ourselves, or not, Moby Dick’s mighty fluke will continue to create waves regardless, whose impact will be felt on shores unknown.