Flint Dille isn’t exactly a household name, but you almost certainly know his work. With more than 30 video game credits, several movie scripts, dozens of fiction and nonfiction books and cult TV shows like Transformers under his belt, Dille is an unsung hero across several entertainment industries.

It all began when as a young man he won a screenwriting competition at film school and landed a job in an animation company called Ruby Spears. He never looked back.

“I was hired to develop new shows and that worked out pretty well, so they hired me to stay on and write episodes,” says Dille. “The first thing I contributed to and and really worked on was a show called Mister T. That was Spring 1983. Things happened quickly. I was on Mister T and did a thing called Robo Force which was my first robot show at Ruby Spears and then went to Lucasfilm to work on a show called Droids. There were two shows — Droids and Ewoks — sort-of Saturday morning Star Wars shows. That was a quasi-disastrous experience.”

Dille’s next job was on the horizon, and would be a career-changing moment. A new trend was about to explode across the toy and cartoon industries, one where the two worked hand-in-hand to create the next smash hit. It was an idea that changed the landscape of kids’ entertainment, and He-Man and the Masters of the Universe was paving the way.

“What was brilliant about it was that they could produce an animated show and then the competitors were forced to advertise on your show,” Dille says. “So they’re doing a TV show which is really a half-hour long commercial for their toys, and then everybody else has to advertise on it and pay me to do my half hour long commercial for my toys.”

“Transformers and GI Joe came out of that environment where Hasbro was saying ‘Hey, we can make toy shows too’. Sunbow was an ad agency. The shows from the point of view of Hasbro were commercials. So they turned the production to their ad agency. And all the ad agency wants to do is sell stuff.”

And to do that they needed the creative talent to make a cartoon that kids actually wanted to watch.

“It was probably autumn of 1984. I'm done with Lucasfilm, Steve Gerber is editing G.I. Joe and he has gotten behind, so they wanted me to come in and give a hand,” Dille says. “I did that for a few months and then the next thing that happened was Sunbow contacted me and wanted me to come on staff.”

“At the time they weren’t happy with the way Transformers was doing and we were competing against a show called Challenge of the GoBots. They hired me and I worked on Transformers as associate producer and the story editor.”

The rise of personal computing, emergence of fandom and the economic miracle of the Baby Boom was converging to alter everyone’s perception of the entertainment business. “At that time I was in the middle of a lot of cultural trends that were happening,” says Dille. “All of a sudden it wasn’t ‘look what those silly kids are doing.’ It was really big business.”

How big?

“When we were working on Transformers it was the year it became the first billion dollar toy line and that’s huge. A billion dollars in the 80s was a totally different thing than a billion dollars is now,” Dille says.

As undeniable as the success of Transformers was, it was also fairly short-lived in that original, episodic formula. Why stop making episodes for a billion dollar franchise?

“We made probably like 300 Transformers and G.I. Joe episodes. With TV in those days you wanted to have around seven seasons. The idea was that then you can could run an episode everyday and you’d have what’s called a syndication package. You have enough episodes to basically cycle through them forever,” recalls Dille.

“We had enough episodes to have a syndication package and nobody was pressed to make more of them. It was kinda expensive and a lot of things were happening at Hasbro and the laws were changing. The whole toy show era we all remember was really a brief period of time. It stuck in everybody’s memory because it was so intense and formative to a lot of kids but it really came and went inside five years.”

The new kid on the block was partly to blame.

“The toys sales were changing, because toys were getting knocked off by video games. The video games systems were getting better and more of the toy dollar was going to video games,” Dille says. “In one way you were really doing well, in another you were seeing doom on the horizon. That was new to that period. Before that, the world wasn’t changing that fast.”

And Dille was right in the middle.

“When I was working on Transformers I was having a great time, but it never occurred to me I would talk about it after 1988. The way fandom works now, it didn’t really exist back then. There were only tiny groups of people who cared about anything that happened more than two years before.”

“I remember going to the Comic-Con in the 80s. There were 5,000 to 7,500 people there, maybe more, but think small. I knew people so I had access that regular people didn’t have, but nevertheless you could walk in, sit around and talk to Stan Lee or Jack Kirby. They were accessible guys who were around, not exotic removed stars.” Dille would say that, of course, having worked with both comic book legends.

“People at Comic-Con were really fans. What none of us knew was that that was gonna become the world.”

Dille makes no bones about the fact he’s been lucky, and talking to him can be a bewildering mix of famous names and chance occurrences. He was forging a path through various industries in flux and, when one door closed, it seems like every time there were others already open.

“Right before the toy show collapse, a guy I knew at CBS had wanted to hire me to develop a show for CBS called Garbage Pail Kids which was going to be one of their first in-house productions. This guy thought ‘we gotta start playing like those syndication companies are playing’. It was the guy who discovered Pee-Wee Herman.”

Anticipating the demise of the toy show model, Dille took the job and transitioned into it while finishing up his last, and perhaps best, series for Sunbow: Visionaries.

“Pretty quickly I figured out it was a disaster,” Dille says about his time on Garbage Pail Kids. “At Sunbow I was playing with one of the best teams that ever existed in animation. These people were incredible. They had a lot of money and they knew what they were doing and all their ideas were new and fresh.”

“As opposed to the network where they were thinking they’re kings of the universe, but everybody else knows they’re not anymore. Everybody knows their time is passing and they have old ideas and they’re really constrained by what you can and can’t do. In retrospect it was doomed, but I’m not sure I knew it at the time.”

That’s when the luck kicked in.

“I just happened to go to a party where I met a studio executive and she said ‘hey we’ve got an animated movie, you wanna come do it?’ It was the kid versions of the Looney Tunes characters. I said I’m not really a comedy writer, and she said ‘yeah, you are.’”

And then one day Dille got home to two messages on his answering machine. With the first he was fired from CBS and Garbage Pail Kids, before the second hired him to write Tiny Toons for Steven Spielberg. What a day! The Tiny Toons gig led straight to a full writing credit on An American Tail: Fievel Goes West and, just like that, Dille was a Hollywood screenwriter.

“At the exact same moment I was working on games. A lot. The games are probably my first love,” Dille says. “I met Gary Gygax in 1982. He got this mansion in LA and so I was going up there and we were working on projects. So whenever I’m not working on Transformers or G.I. Joe I’m at this mansion.”

“We were designing game modules, writing movies, we made a series of books that you can actually still find about a character called Sagard. Gary had a 16 by 6 foot sand table and and 3,000 medieval miniatures so we were playing Chainmail, which is a miniature game that had first led him to Dungeons & Dragons. We were playing games, working on games, learning how to design them. What was great was that my other writing stuff was paying for that, so I just treated it like a game design school.”

Dille recalls fun times at the Dungeons & Dragons mansion, but it’s said that he and Gygax worked on a movie script together. Was it for D&D?

“We did not write an actual D&D movie script because we couldn’t,” laughs Dille. “A guy called James Goldman had been paid a lot of money by TSR to write a D&D movie. It was kind of clogging the world up, so Gary and I were writing about different stuff and we wrote most of a script called 'Scepter of Seven Souls'. I don’t think we ever finished it, but we went out, pitched it, we met with Orson Welles, whom I would work with two years later on Transformers. It was just a really fun period.”

The script would never make it into production, but Dille’s time with Gygax had whetted his appetite for working professionally on games. He felt he had a new understanding of how they ‘clicked’ with players, and it was time to turn that knowledge into a brand new career. The beginnings were humble.

“I worked on a bunch of games that either didn’t get made or didn’t get made in recognizable form or got made but never released,” Dille laughs. “The first time when I was paid to work on a video game was a thing called Isix in the late 80s. Isix was a technology that gave you four paths on a VHS tape to make an interactive movie with a little bit of gameplay.”

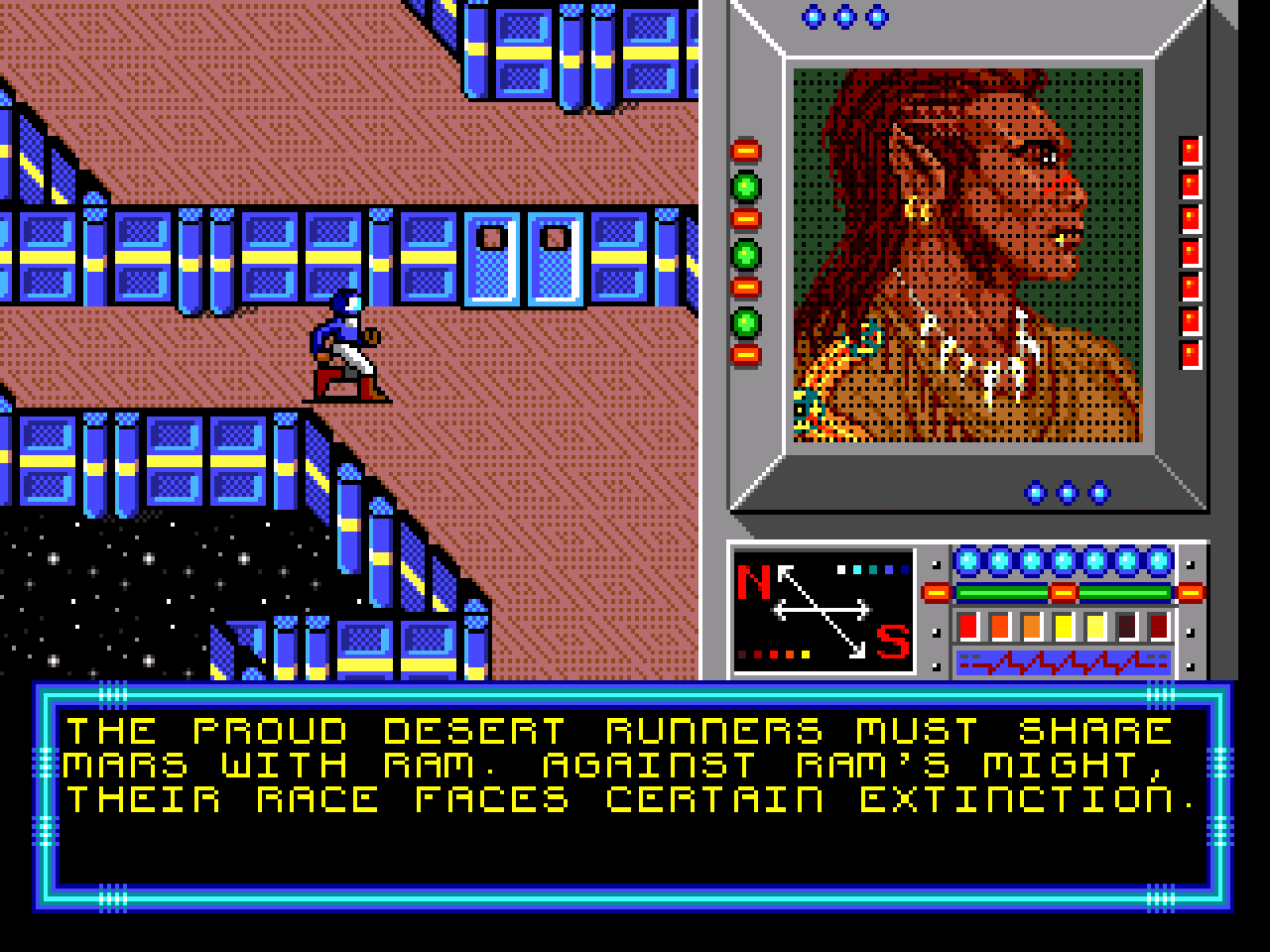

“The first thing that I worked on that got released and sold was probably Double Switch for the Sega CD. There was also a Buck Rogers game called Countdown to Doomsday, and that was a pretty classic computer game that people remember well.” Flint wasn’t the first Dille involved in the Buck Rogers franchise: his grandfather, John F. Dille, had helped turn it into an immensely popular comic strip in the 1920s.

“The first really big title where I started thinking of games as a way to make a living was Soviet Strike for EA,” Dille says. “Soviet Strike was made for PlayStation and nobody expected it to do well. EA just wanted to give Sony the impression they were supporting them. They took it seriously financially, but EA was doing extremely well at that time so they could afford it. But you just didn’t get any sense of confidence from the execs. They didn’t really wanna be around it.”

Yep, you guessed it, a classic underdog story.

“It came out and was the highest selling CD game ever made to that date. We did Nuclear Strike afterwards. That took me into the late 90s. When the 90s began I was a screenwriter who sometimes did games, and the decade ended with me being the game guy who sometimes did screenplays.”

It wasn’t long until the new path led Dille to some high-profile gaming jobs. In the early 00s Starbreeze and Vin Diesel came knocking on his door, offering the chance to redefine what a game based on a movie could achieve.

“Chronicles of Riddick: Escape from Butcher Bay was a really good experience,” says Dille. “We didn’t come in until Vin had rejected the script and the design for the first iteration of the game. And we kinda did a redesign and a rescript and revisualize the story. Vin was the real deal, he was there for the whole thing. He had a lot of ideas. This game wouldn’t have been anything like the game you know, had it not been for him.”

Did Vin Diesel geek out at working with someone who knew Gary Gygax?

“I don’t know how we got on the subject but in my first conversation with Vin he was telling me all about his level 60 half-elf drow mage,” Dille laughs, still in awe of Diesel’s geek cred. “I’m looking at him and at this point I’ve been doing stuff for TSR [publisher of D&D] for almost 20 years, I’d seen every level of game fanatic there was and I’m looking at him and thinking this guy is hardcore. He’s the real deal.”

“Here's what’s funny. I didn’t know what a drow was at this point. I could fake my way through a conversation. I wasn’t totally clueless. But I sent Gary an email asking ‘Gary, what’s a drow?’ And he explained it to me and said ‘why?’ And I said ‘well, Vin Diesel is telling me about his half-elf drow mage called Melkor.’”

For the record, the drow are “a generally evil, dark-skinned, and white-haired subrace of elves.”

Years later Dille and Diesel were In The Vinmobile, an SUV with the satellite dish on the roof for the purpose of playing World of Warcraft on the move, when two worlds Dille knew collided.

“We were sitting there and he was downloading patches, so he could show me the new content. It was exactly right after Gary Gygax died and the patch that he was downloading was a tribute to Gary. It's a small world.”

***

Among the famous properties Dille has contributed to are James Bond, Mission Impossible, Scooby-Doo, Diablo, Uncharted and Batman. That last one even earned him a spot in The Guinness Book of Videogame Records for creating the first Batman villain outside of the comics in Batman: Rise of Sin Tzu. Despite that, he knows his place in the greater scheme of things.

“I realize going into a license property that I’m a parasite. My going in and rebooting — and it’s my least favorite word in the entertainment lexicon — something is usually gonna make it crap and it doesn’t make it mine and doesn’t mean I’m not a parasite.”

I ask Dille about the transition from writing cartoons to movies to video games, and how he feels about the way stories in interactive media have evolved thus far.

“A lot of our early game storytelling, and a lot of it still and not all of it invalid, is based on conventions from prior mediums. It’s based on movie conventions, TV conventions, and that’s OK,” says Dille.

“Games started basically like the movies where all the actions scenes were the gameplay and the cutscenes were the dramatic scenes. That’s one way to approach it. And for all the people have maligned that, people sure had a lot of fun playing games that were structured exactly like that. That was one phase and I think that it’s to this day a legitimate way to approach game storytelling. Is it the most novel way to approach it in 2017? Probably not, but new isn’t necessarily better. I don’t believe there’s one way to do anything.”

“What can you do in this medium that can’t be done in any other? Any storytelling technique can work, but does it fit the material you’re trying to tell the story about? You’d better enjoy it or don’t be in the business, because you have to get your hands dirty and poke around and see what’s actually there. Cause a lot of things aren’t what they appear to be.”

Dille praises the work of Marvel, Telltale, Naughty Dog and DC, but admits that solving his latest challenges leaves little time to properly appreciate the work of others. Dille’s current role is Creative Lead at Niantic, the makers of alternate reality hits Ingress and Pokémon Go (“I’ve had a very lucky career”) and he’s on the lookout for the next big idea.

“Right now I’ve been working on AR game world. We’ve been telling the story pretty much in an old AR way, and I’m trying to figure out how do we do this better. What’s the 2019 version of this kind of storytelling? That’s what’s keeping me awake these nights.”

Whatever that next big thing may be, you get the feeling Flint Dille will be somewhere near it.