Below is a real map of a fictional place. The volcanic island of Vvardenfell in the province of Morrowind may not exist, but that doesn’t diminish this map's reality. You can take it out while playing the game and it’ll help you find your way. You can study it to plan your next route. You can take it out of its dusty box years later, reminiscing about the places you used to visit. The magic of video game maps is that they constantly shift and redraw borders between the real and the imaginary.

To modern eyes this is also more of a 'real' map than, say, the kind of medieval maps that show Europe, Asia, and Africa in such an abstracted way that they’re barely recognisable. It’s more useful for navigation, at any rate. Of course maps serve many purposes, and helping you on your travels or representing topography are just a few. Some maps present a conceptual view of the world, for example according to medieval Christianity. The Vvardenfell map doesn’t merely show routes and topography either, but also various architectural styles of cities and fortifications: hinting at its various factions, cultures, and their seats of power.

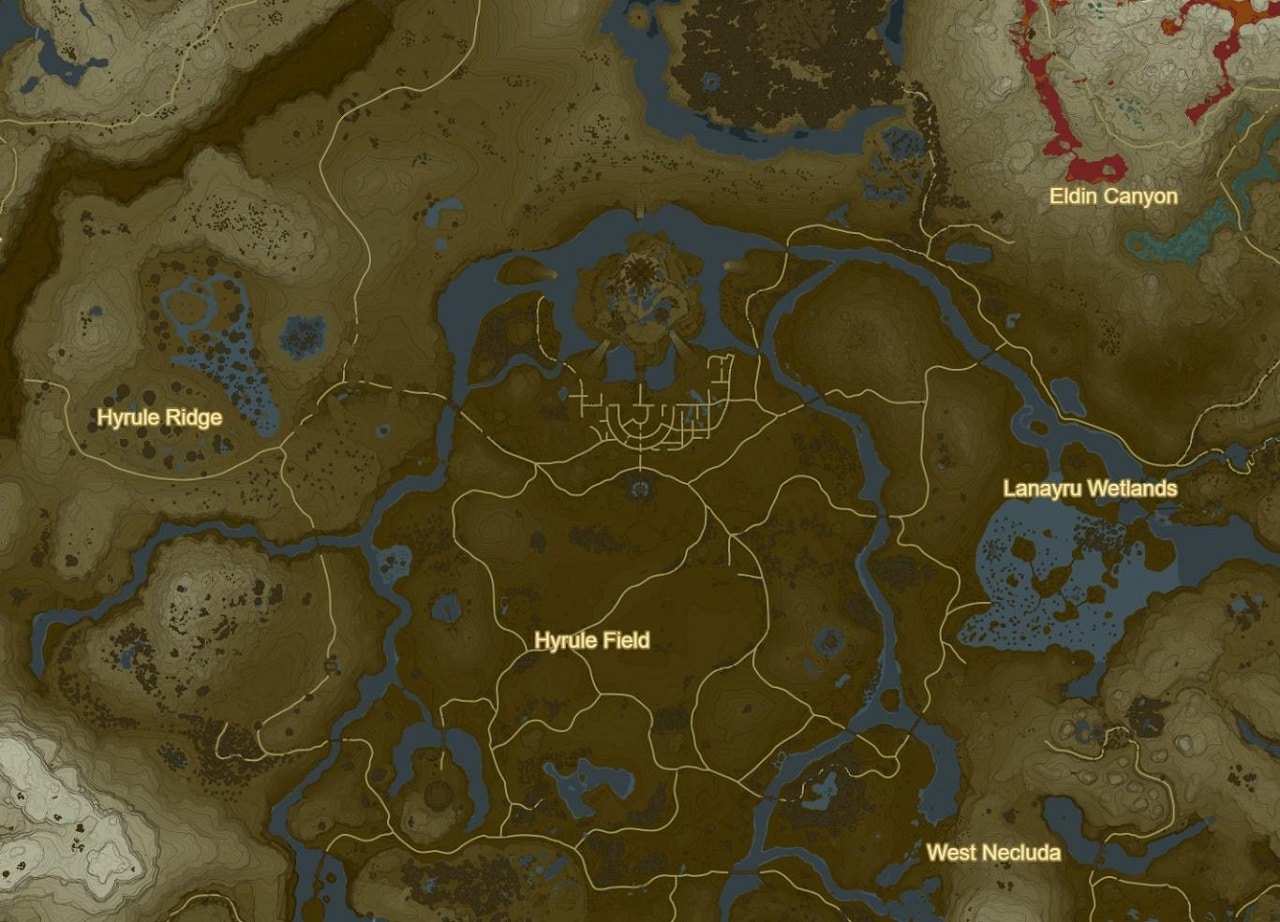

If you hear 'video game map', you might think of open-world games and RPGs, and those sprawling maps that try to encapsulate whole worlds in a glance. Breath of the Wild delivers a map that rejects aesthetic flourish in favor of simple elegance — it is uncommonly sparse and reluctant to provide much information about what lies hidden in its world. While its topography is presented in impressive detail, with contour lines and shading indicating elevation, it is careful not to compete with the visual splendour of the world it represents. Its spatial hierarchy, too, is noteworthy, with Castle Hyrule visually dominating the map, centred and slightly elevated. It recalls Morrowind’s ominous Red Mountain and, like Jerusalem in many a medieval map, these seats of power claim the navels of their worlds.

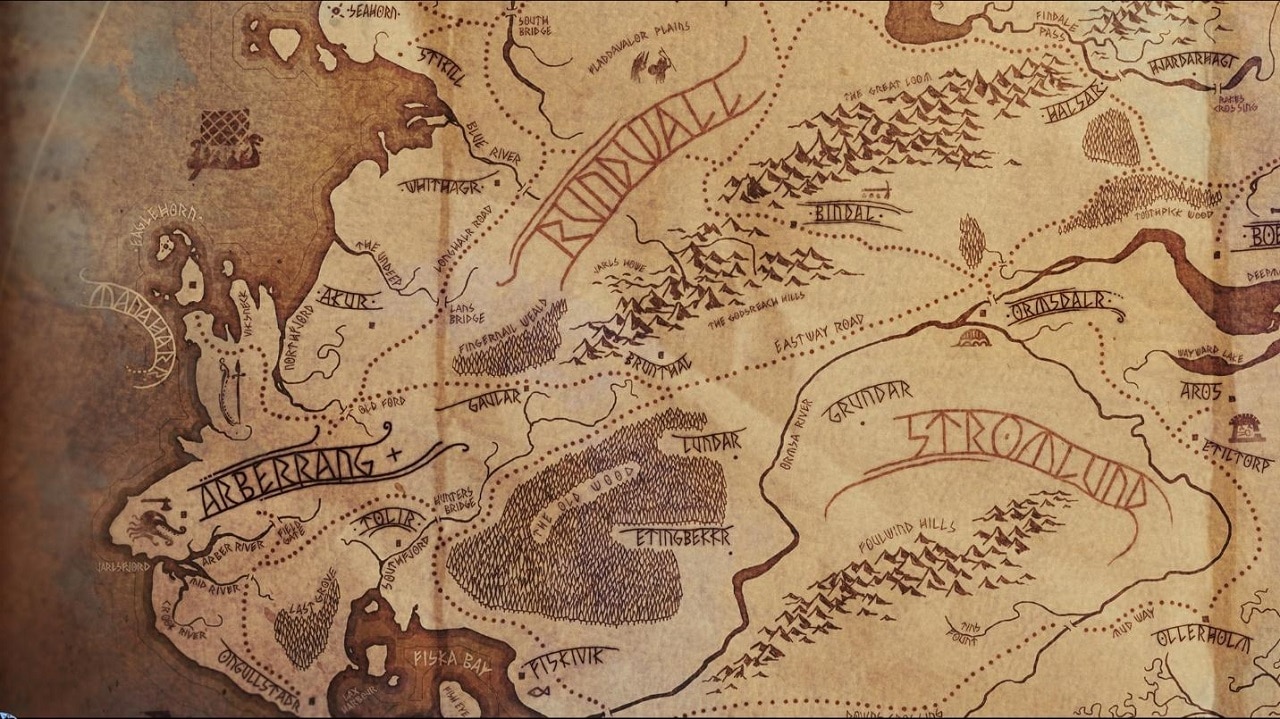

The maps of The Witcher 3, beautiful when they aren't covered in icons, rejects these hierarchies for a more naturalistic look. In keeping with the realist tone of the game, they present glimpses of landscapes that seem grounded in earthly topography. Like Breath of the Wild, it rejects ornamentation, but its details and slightly painterly feel invite you to linger.

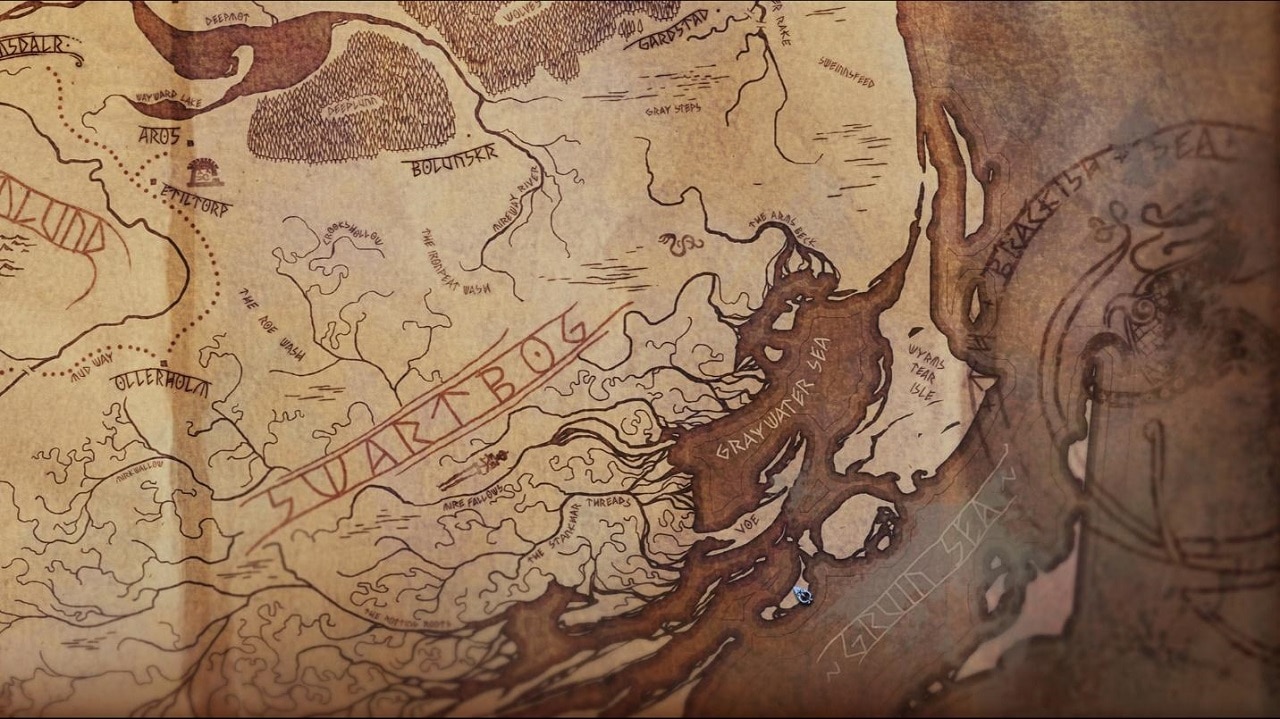

Maps like those of The Banner Saga or Tyranny also evoke the scale of grand fantasy worlds but, since these aren’t open-world games, they are free to ignore tedious topographic detail in favor of visual playfulness and flourish. They are impressionistic rather than literal. The artfully cartoonish map of Tyranny bears the seal of Kyros the Overlord, and is encircled by a frame that contains the warlords of this battle-torn world. The map of The Banner Saga has many ornaments too, from star constellations and ships to Norse dragons and tiny warriors. It also serves as an encyclopaedia: clicking on cities, forests, roads and more produces information about places you may never visit over the course of the game.

These maps even have a material dimension: In Tyranny’s strong opening, we see this map on a table, with various tools and metal pieces representing armies and cities on top. The winner in this regard, however, is clearly the worn parchment map of The Banner Saga with its faded, irregular ink, discoloration and even folding marks.

Fantasy games with their grand worlds aren’t the only ones interested in the tactility and physical presence of maps. Especially in games from the immersive sim tradition, maps do not simply depict spaces; but are a material, localized part of the spaces they depict.

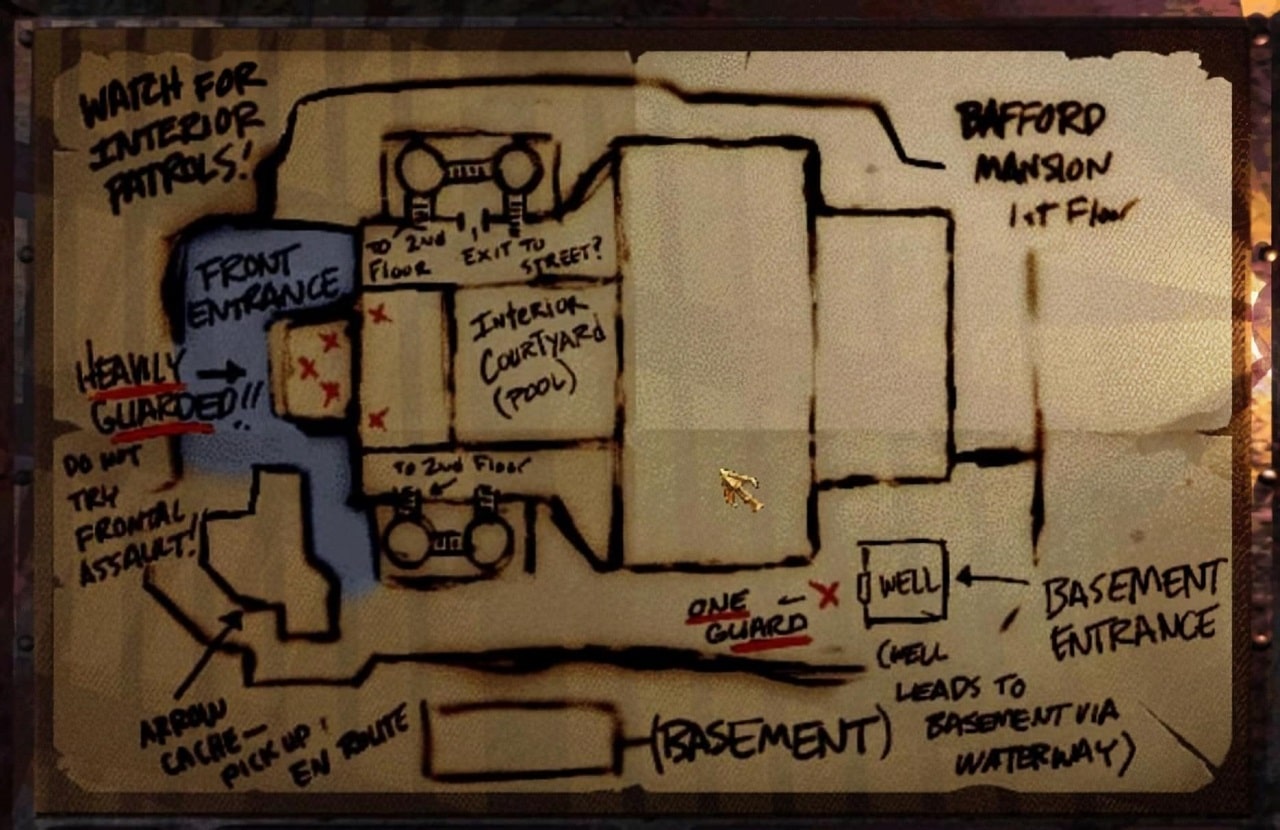

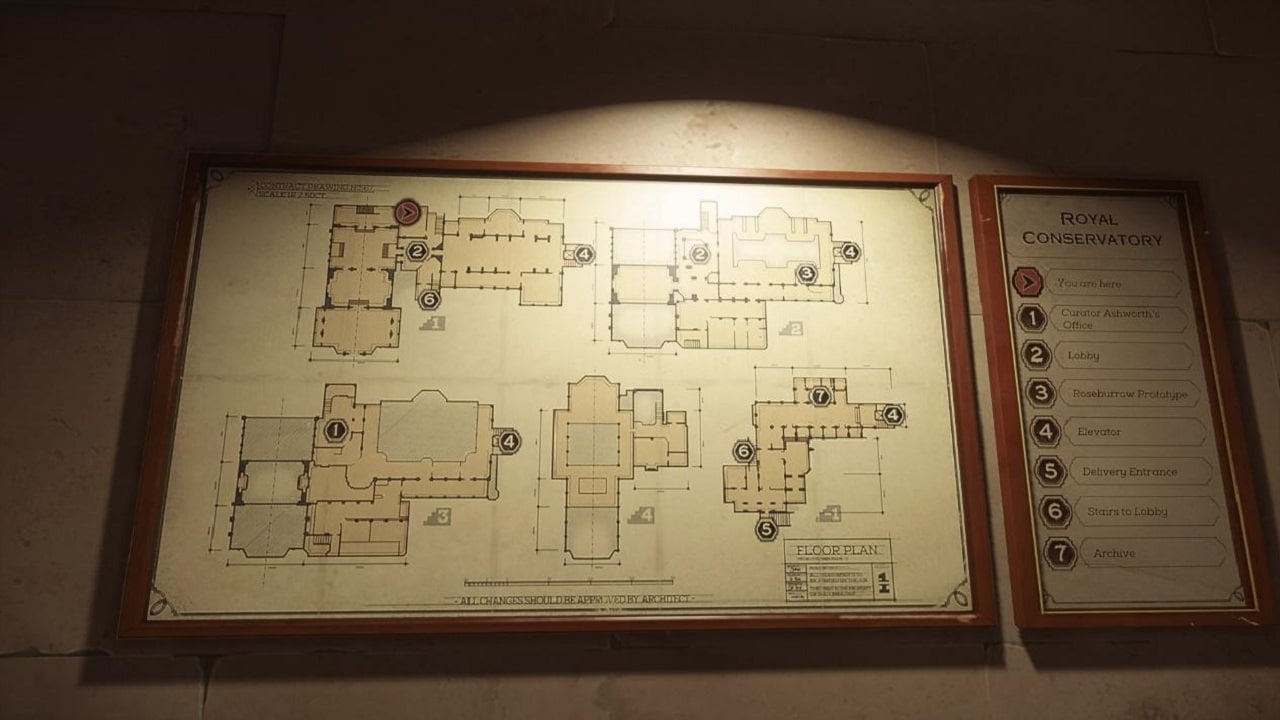

In Thief: The Dark Project, you are an outsider and criminal, and thus don’t have access to complete maps of the places you infiltrate. Instead you make do with improvised, makeshift maps full of guesswork, empty patches and annotations hinting at dangers and possible routes. The Dishonored games provide you with more objective maps, but you must find them first.

Just like in real-world public buildings, plans to these complex architectural spaces can be found on walls if you know where to look. There are less directly practical maps as well, such as globes or embossed maps of the isles, that don't just hint at a wider world but show how these people perceive it.

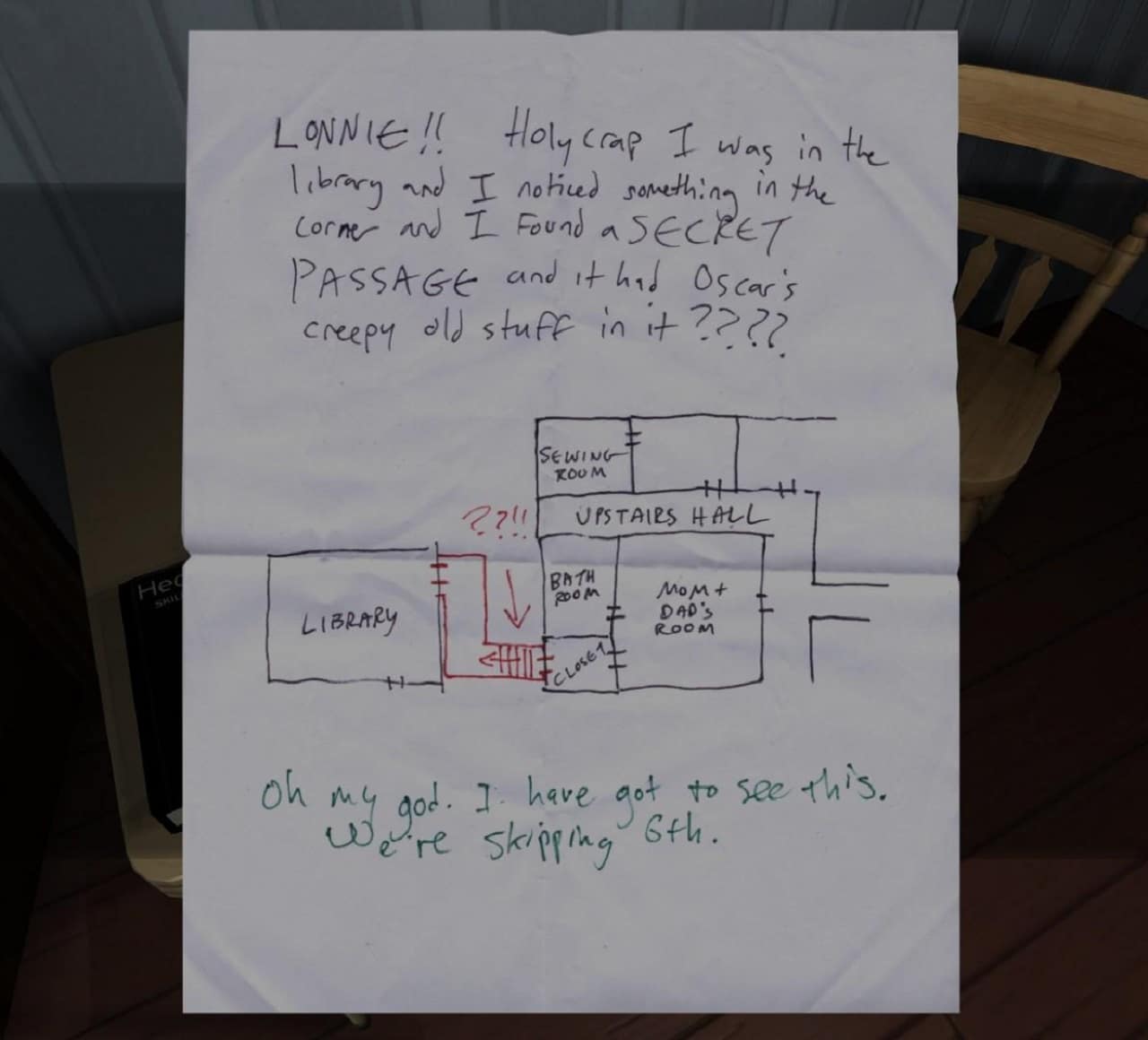

Gone Home and Firewatch are often called 'walking simulators', but their roots in immersive sims are laid bare in the maps. Gone Home does have a run-of-the-mill map accessible from the menu, but hastily-drawn maps reminiscent of Thief can be found all over the mansion.

Some, like a note titled “Directions to work from new house”, have no practical use, but tell you something about the life of this family, while also suggesting inaccessible spaces outside the house. Others, like Sam and Lonnie’s doodles of the house, guide the player and reveal hidden details in a playful and organic manner.

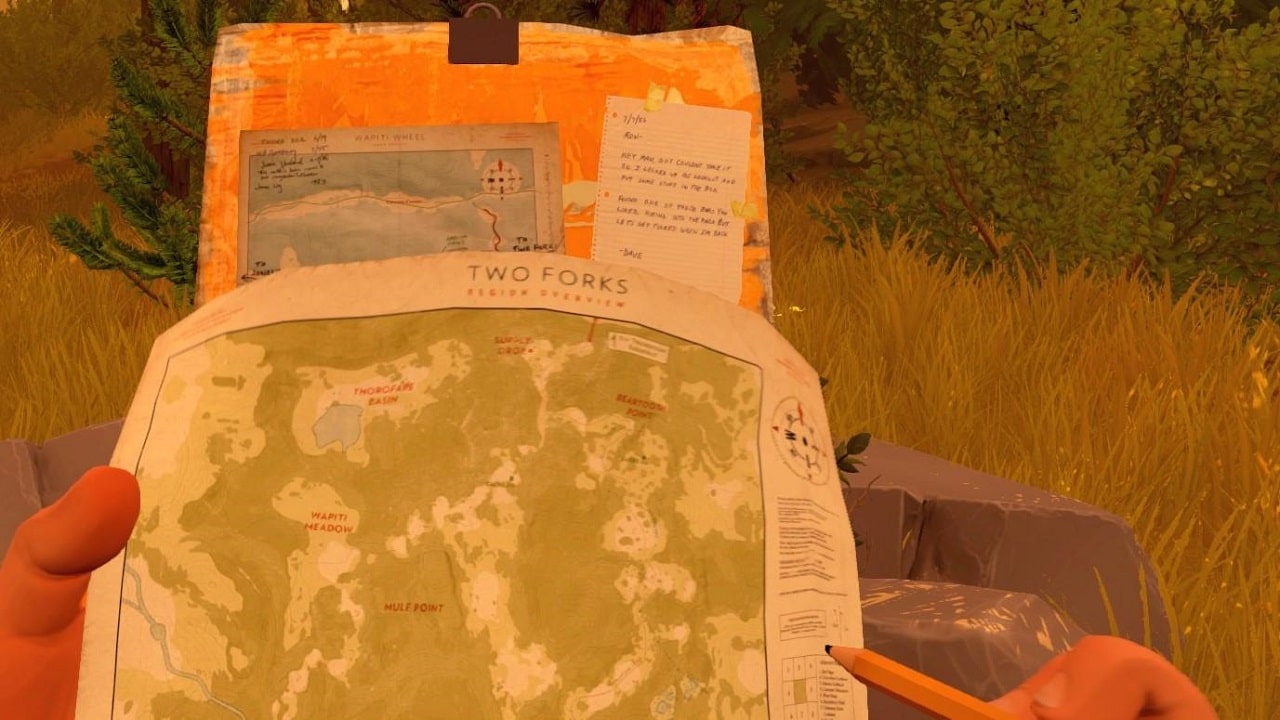

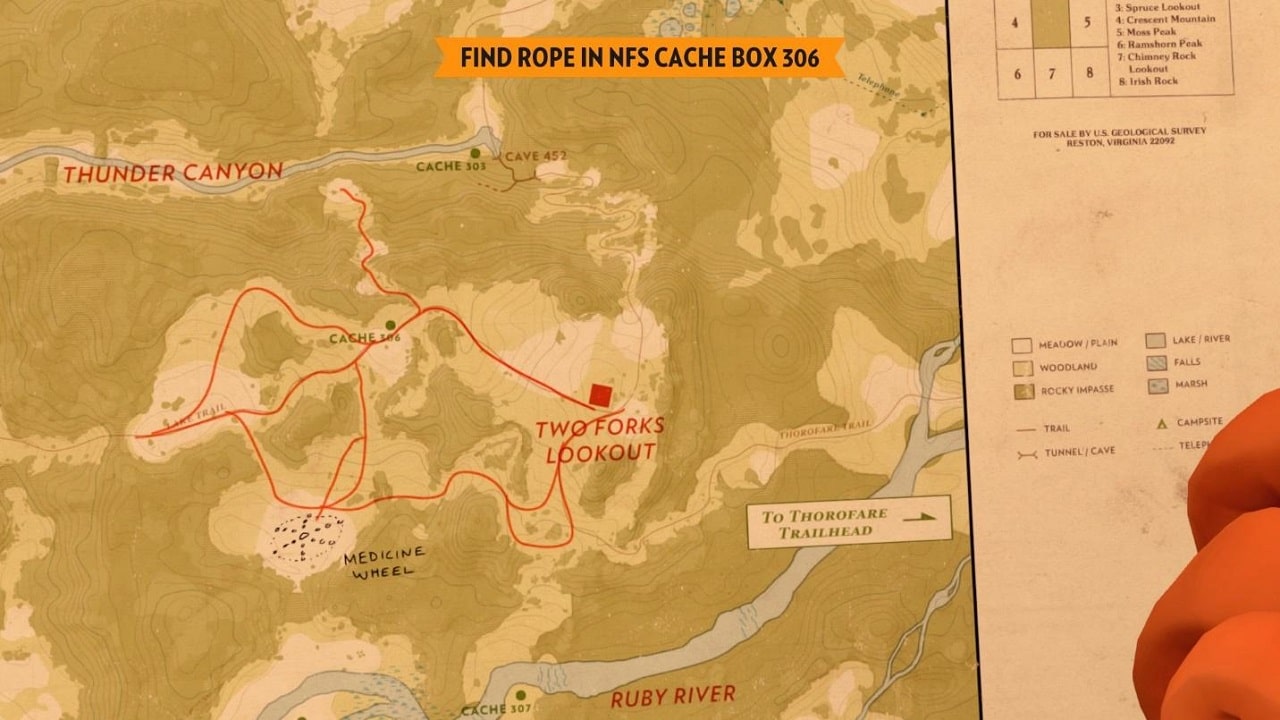

In Firewatch, the map of the Two Forks region takes center stage. At any time Henry can take out his map and compass, which appear not in a disembodied menu but in his hands as physical objects. It’s an attractive map, but it’s the material details that really make it: the texture of the paper, its slight wear-and-tear, the imperfect print, the detailed information printed in the margins, and the way the paper bends when Henry moves while holding it. And, like a famous example from the Silent Hill games, this map too is silently updated and annotated as you progress through the game.

In the 2012 title Miasmata the protagonist must also hold map and compass in front of him to find the way. It’s less of a looker than Firewatch’s map, but the way you interact with it is far more interesting. To fight the horror vacuum and fill in the blanks, you need to triangulate your position by finding two known landmarks (e.g. a statue whose location is already marked on the map) in the distance. It’s tricky business that demands spatial awareness like few other games, but the pay-off is a uniquely intimate player-map relationship.

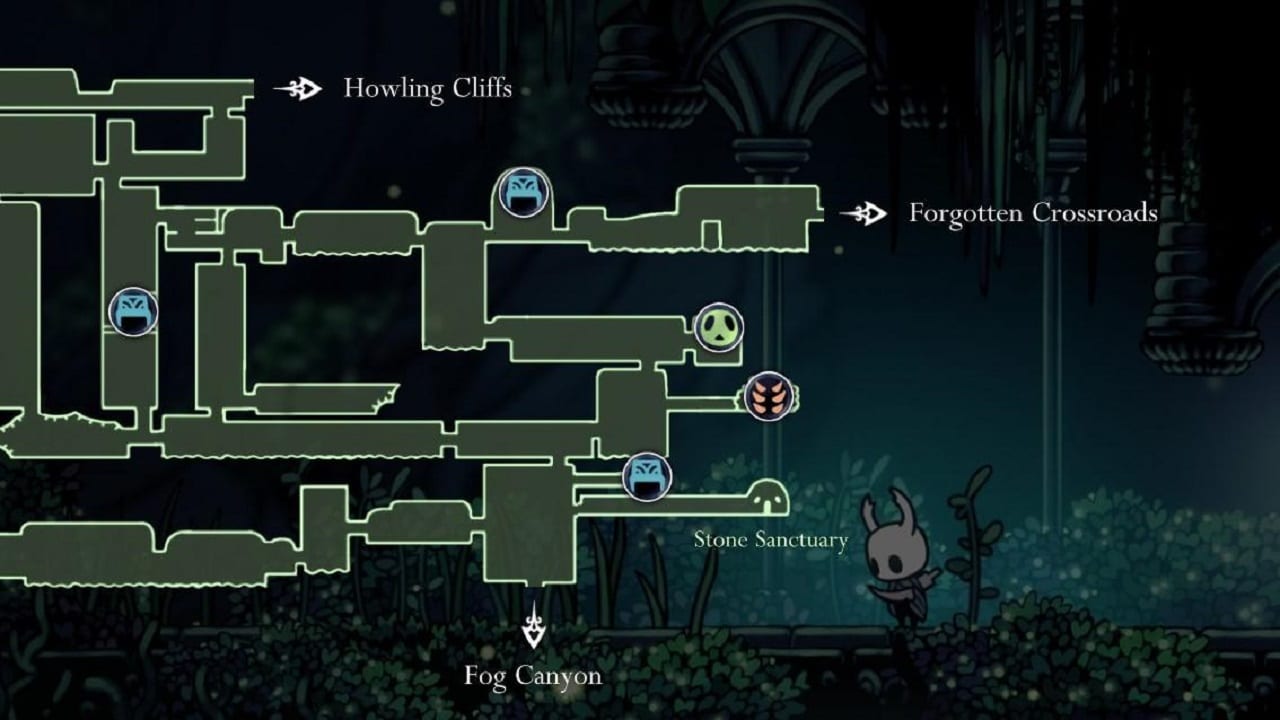

Games in which players must participate in cartographic work are few and far between, but the exceptional Metroidvania Hollow Knight captures some of Miasmata’s spirit on a 2D plane. To unlock the maps of individual regions of its enormous labyrinth, you first must find the wandering cartographer hidden in every area. Once you’ve bought his map for a modest fee, you’ll have access to a very rudimentary map that leaves out many details and even entire rooms. To fill in the blanks, you must complete it: first visiting individual rooms, then returning to one of the benches that serve as checkpoints. Only then will you have a detailed picture of the rooms you already discovered.

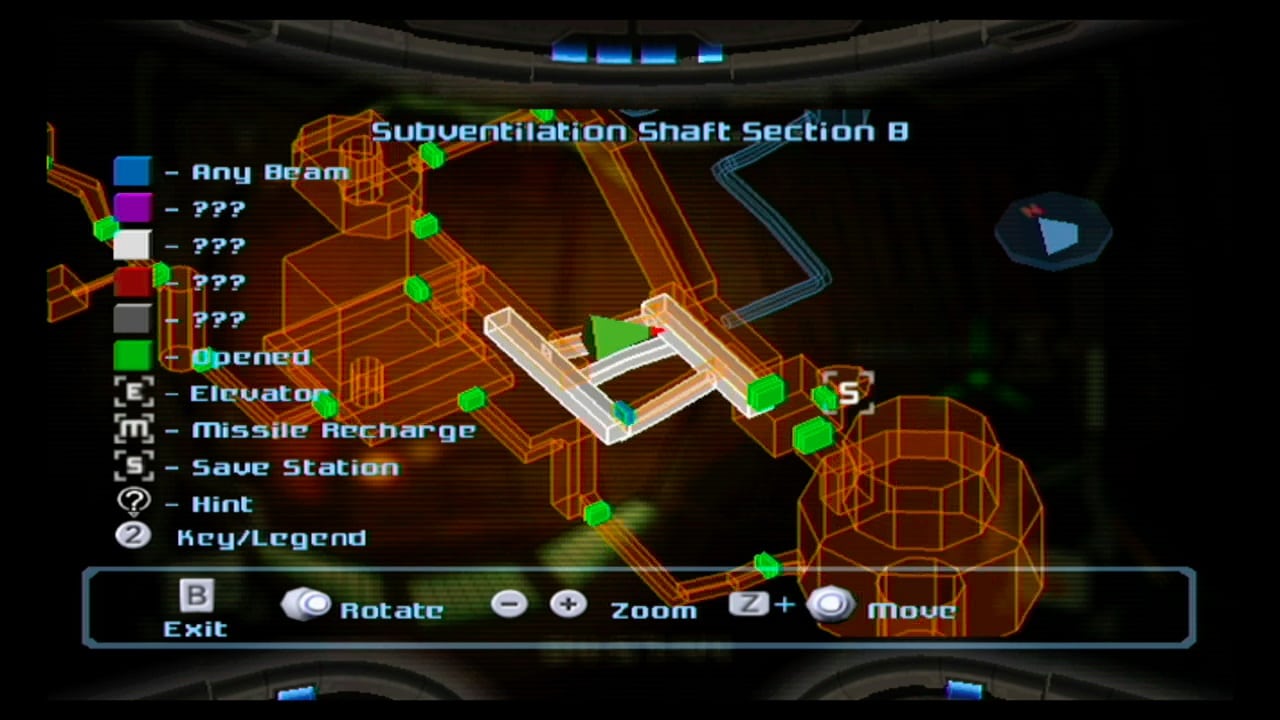

Mapping labyrinthine spaces in 3D is a difficult task, and Metroid Prime is still one of the most impressive attempts. As in Miasmata and Hollow Knight, there’s a lot of interaction between player and map, but the main interaction in Metroid Prime isn’t so much filling in previously unknown spaces, but simply studying the complex interconnections of an alien maze by rotating and zooming into a three-dimensional map that manages to be both challenging in its complexity and elegant in its simplicity. Unlike Firewatch or Miasmata, there’s nothing tactile to this map, but since it seamlessly fits into Samus’ interface, it still feels like an integral part of this high-tech world.

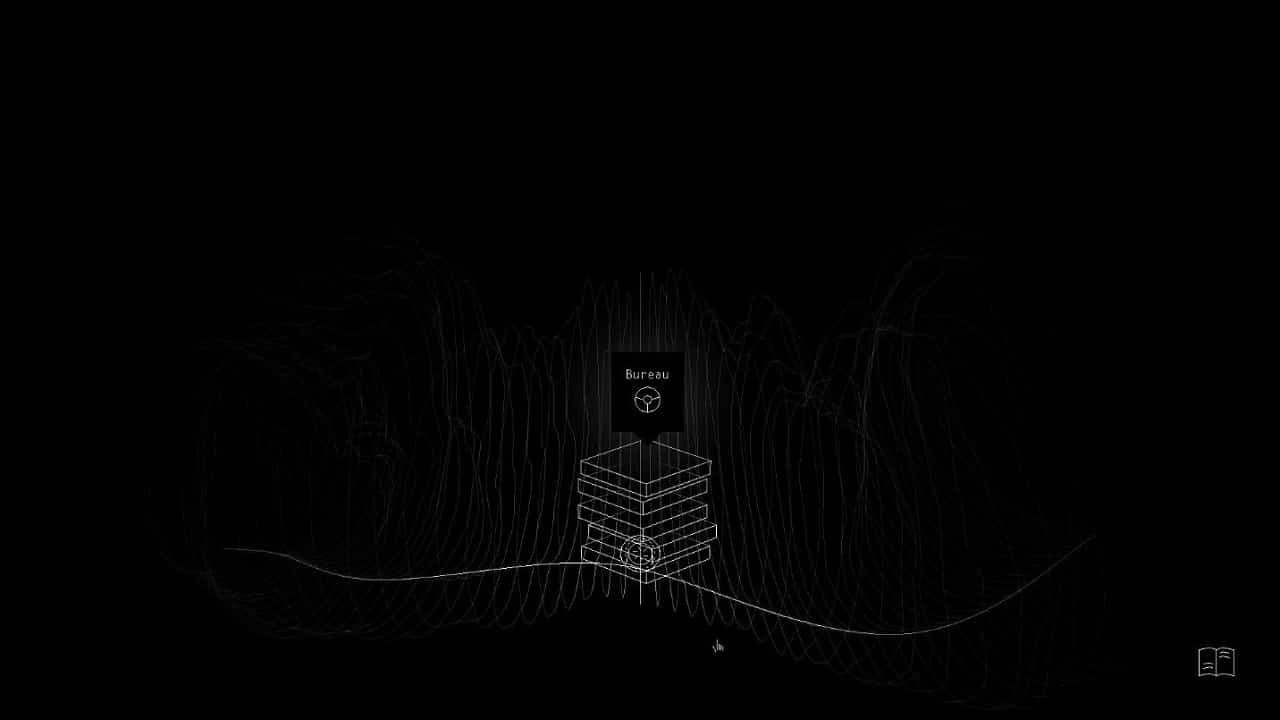

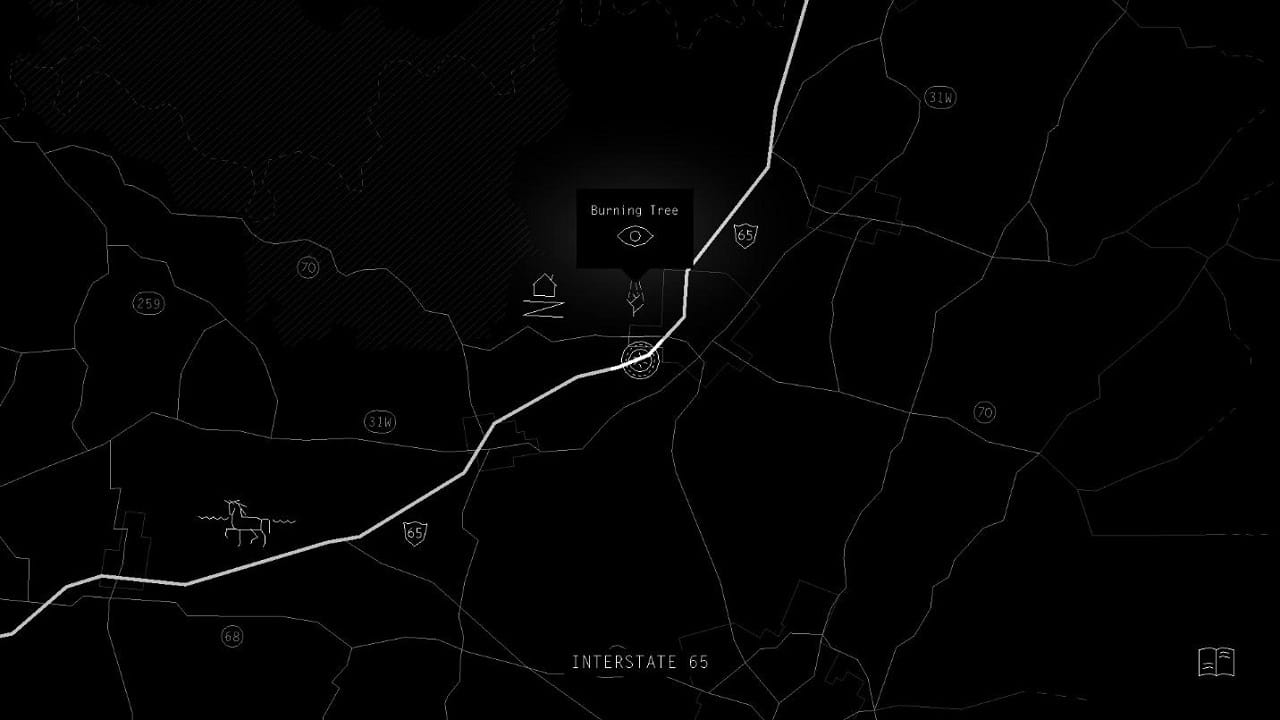

Maps are a staple of mainstream games, but have a place in experimental games too. Take Kentucky Route Zero, whose dreamlike, fragile maps are nothing but the faint white lines of streets, rivers and ominous symbols suspended over a black plane that resembles an abyss rather than a landscape. Its maps don’t signify coherence and knowledge, but discontinuity and fragmentation.

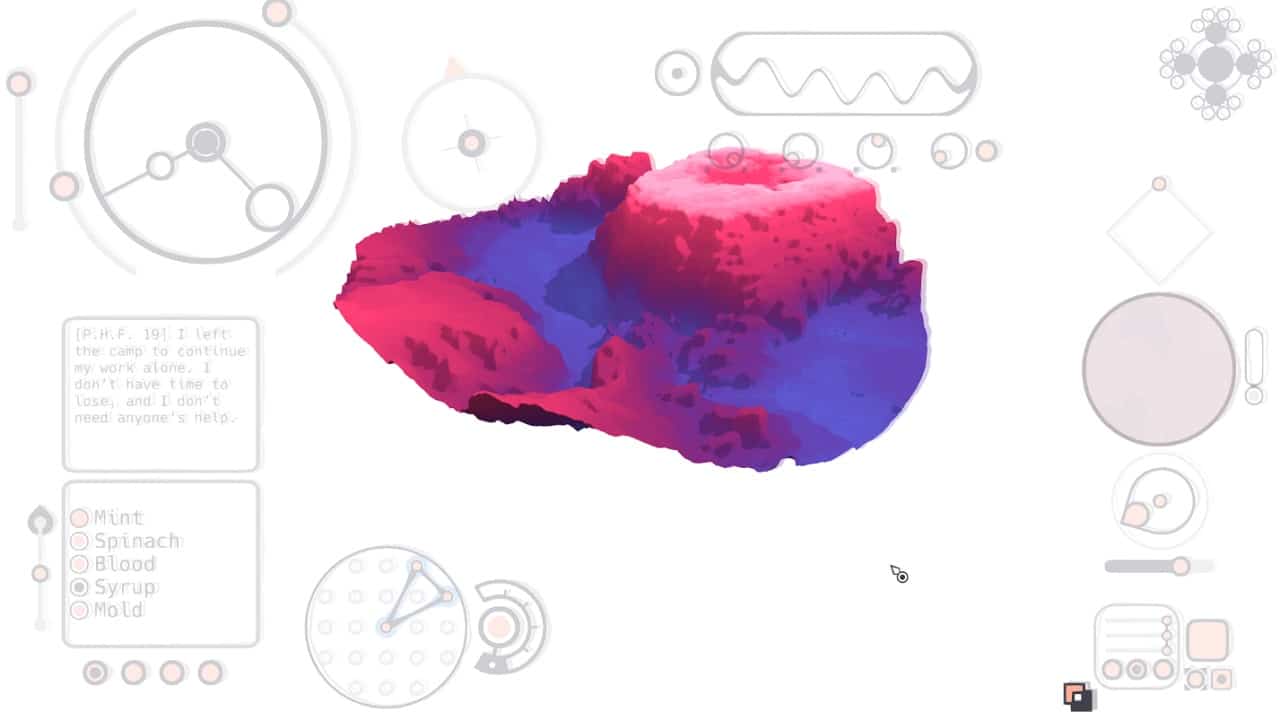

By contrast, Mu Cartographer displays a rich topography. These landscapes are inconstant, however, and can be changed in dramatic ways simply by adjusting the myriad parameters; they shift and flow, mountains sinking into the ground, canyons moving by like waves, strange architectural structures rising from the depths. The maps of Kentucky Route Zero and Mu Cartographer share a skepticism towards the cartographic promise of encyclopaedic knowledge. They have been detached from any landscape either real or imagined and drift through an in-between realm. No matter how long you play, these spaces remain distant and dreamlike.

There are other ways to play with the ways maps and landscapes relate to each other. In some games, the distinction between the two vanishes: landscape and map are one, or flow into each other. This is the case in the naval RPG Sunless Sea. The islands, ports, and geographical structures are static, schematic and labelled as they would be on a map, even as roaming boats and sea creatures bring this map to life.

More often, though, this effect belongs to the turn-based or grand strategy games. The map-landscapes of Europa Universalis IV are like a colourful historical clockwork atlas that changes not through the turning of pages, but the calculations of a deep simulation. At any time, you can change the overlay of this map, from topographical to political, from commercial to religious, and gain insight into various parallel states. One map contains a multitude of overlapping maps.

The beautiful maps of Endless Legend, by contrast, are assembled procedurally. Its basic makeup of hexagonal tiles gives its maps a tactile model landscape feel, with structures and mountains popping out, but if you zoom out far enough the model changes — into a paper-like map with minimalist drawings of trees, cliffs and waves.

There are many other kinds of map in games. Star charts. Maps not of spaces, but of thoughts or human relationships. Maps merely imagined while trying to understand a virtual space, or carefully drawn on a piece of paper. Their effects are as colorful and various as the maps themselves: some do it for aesthetic reasons, some for immersion, and others perhaps to make you think about the nature of maps, or the ideologies from which they grow. The most fascinating maps are those that recognize the peculiar space they occupy, and play with the tensions between the real and imagined, the seen and the unseen. Rich as our current landscape may be, the future is vast and uncharted.

Shopping Cart Returner Shirt $21.68 |

Nothing Ever Happens Shirt $21.68 |

Shopping Cart Returner Shirt $21.68 |