There’s a lot of unnecessary mystery surrounding video game pricing. In the UK, we can often feel short-changed: we look at what our American friends pay in dollars and wonder, why am I paying the same in £? Or we take a peek at digital storefronts like PSN and bristle that the latest games are actually more expensive than they are in shops.

There are some simple and not-so-simple reasons for all of this. It’s complicated by the fact that so many publishers and retailers are extremely reluctant to talk about money, and especially about what happens to that money once you hand it over for a game. For no particularly good reason that I can think of, the machinations of the system are shrouded in secrecy. I was unable to get a single UK retailer or publisher to comment on the record for this article, for instance, not even on something as innocuous as where the money goes when we way £50 for a game. The idea here is to get those systems out into the open, and clearly explain the factors that determine the price we pay.

In short: if shops and publishers won’t explain why we pay what we pay for video games, we’re going to do it instead.

Why is it that digital versions of games often cost as much as - or more than - physical versions bought in shops?

The relationship between publishers and retailers has been at the heart of how the games industry operates since the 80s. The truth is that this relationship is what largely determines why you pay what you pay for games: it defines both in-store pricing AND digital pricing. Publishers, for reasons we’ll go into later, quite literally cannot afford to undercut or otherwise piss off retail under any circumstances. That’s why, for instance, FIFA is the same price on Xbox Live and PSN as it is in the shops (or even more expensive, at £59.99), despite the absence of distribution and packaging costs.

Here’s the thing: a huge percentage of games, especially the biggest ones, are still sold in shops, whether through large chains like supermarkets or specialist stores like GAME. Publishers’ relationships with these retailers, and their buyers, are extremely important. Publishers regularly take these buyers out to show them their new products, mostly in meeting rooms, occasionally on lavish trips (expensive press trips might have died a death since the mid-00s, but I can assure you that expensive publisher showcases for retail certainly have not). The idea behind all of this is to persuade retailers to stock the products, and give them prominent placement on the shop floor, in order to sell more copies.

Imagine, then, that EA comes along and decides to sell FIFA 16 for £30 on the PSN or on Xbox Live, and for £45.99 in a chain of shops (let’s call it GameShop). On the face of it this would make sense: selling through PSN, there’s no manufacturing or distribution cost, and EA doesn’t have to pay a retailer (though it does have to pay Sony). But then GameShop would be furious, because customers would flock to PSN to buy it online for a cheaper price, resulting in less money for GameShop itself. GameShop wouldn’t stock EA’s next products, or would threaten not to, or would demand a bigger cut of sales, or promote the products less, and EA would lose out on too much money.

Games still make most of their money in the first few weeks after release, so presence at retail is vital. “For the publishers it’s driven by the amount of time they have to make back their money,” said Joost van Dreunen, who runs SuperData Research, a company that analyses game markets. “On a big 100, 200-million-dollar launch, they only have 2 to 3 weeks to make back their initial investments. So it’s key for publishers to have their boxes on display at the center of the store. It’s all about the real estate inside the store.”

If you’ve ever wondered why new games on digital storefronts seem arbitrarily over-priced, that’s why. Publishers can’t afford to adjust the RRP, or the relationship with retailers would break down. This is also why buying games through Steam is so much more cost-effective: nobody sells PC games in actual shops any more, so there are no retailers to piss off by pricing things lower. (And also, nobody has to pay a licensing fee to any platform holder, like they have to do on PlayStation or Xbox. Even when PC games were sold in shops, in the ‘90s and early ‘00s, they were cheaper for that reason.)

Aha. Is this why publishers are so keen to push their own storefronts? I’m looking at you, Origin.

Yes. Selling through their own digital storefront is a publisher's dream, but right now it’s not at critical mass. They still rely too heavily on retail.

“I know that EA is now 49% relying on digital revenues at least in the last couple of quarters [of 2014],” Joost told me. “For Take 2 that’s 32 percent or so. Activision is roughly the same rate and Ubisoft is about 8 to 12% relying on digital. If you compared it to five years ago, that percentage was much, much smaller. They’re trying to figure out how to become a little bit more competitive with physical retail distribution by exploring digital.”

So where does the money go?

This is something I think we’d all like to know: how much of the purchase price actually goes to a developer?

Naturally this varies by platform. Buying digitally from Steam or an independent online retailer? The retailer takes about a 30% cut and the developer gets the rest. Buying direct from a developer? That’s all for them. But how about a boxed game, bought in shops?

From what I’ve been able to find out, generally a retailer in the UK or the US will take 20-35%. This will often be negotiated, especially on big launches: a publisher might offer a bigger cut in exchange for really heavy in-store promotion to drive sales. If you see a game retailer REALLY pushing a certain game, either through pre-order or once it’s on sale, it’s likely that retailer has struck a good deal with the publisher and stands to make a lot of money if it sells well.

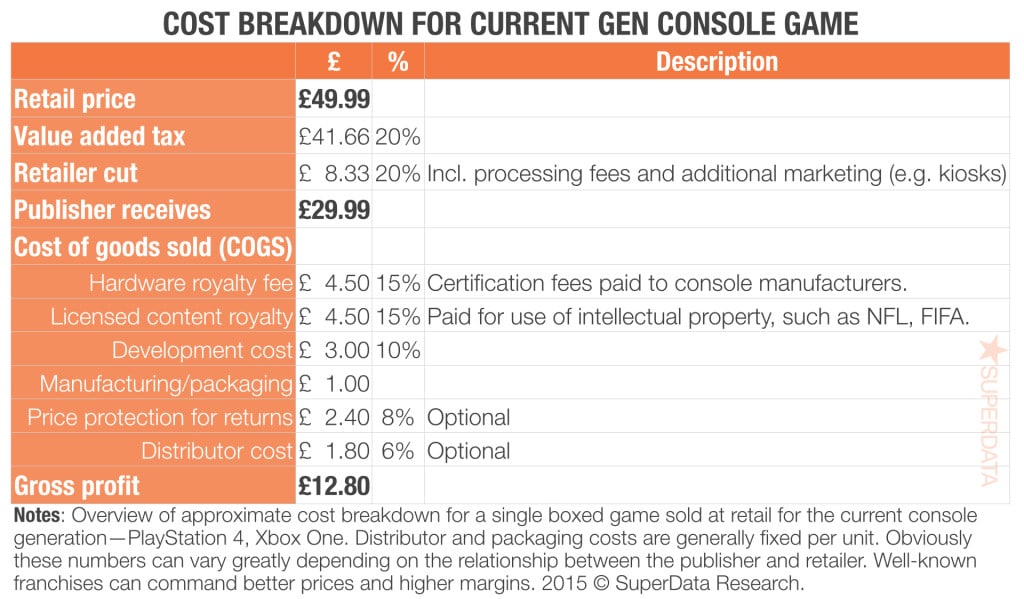

As for what happens to the rest of that money: SuperData put together this useful infographic that visualises where it goes, as an estimate. Depending on the game and the retailer, of course, it could look very different.

TO BE CLEAR: all of the above varies. Actually, everything varies. I’ve run this breakdown by a few people and a lot of them think the retail cut is a bit low - though of course, it varies by retailer, and by the deal. I have heard - but not been able to substantiate - claims that the retail cut of a game in the UK is closer to 40% or 50% in some cases. I have heard retail described as “a fricking labyrinth of kickbacks, multi-game deals and God knows what else, and you can never get a straight answer because there are so many facets to any particular deal.” Totally familiar with that last part.

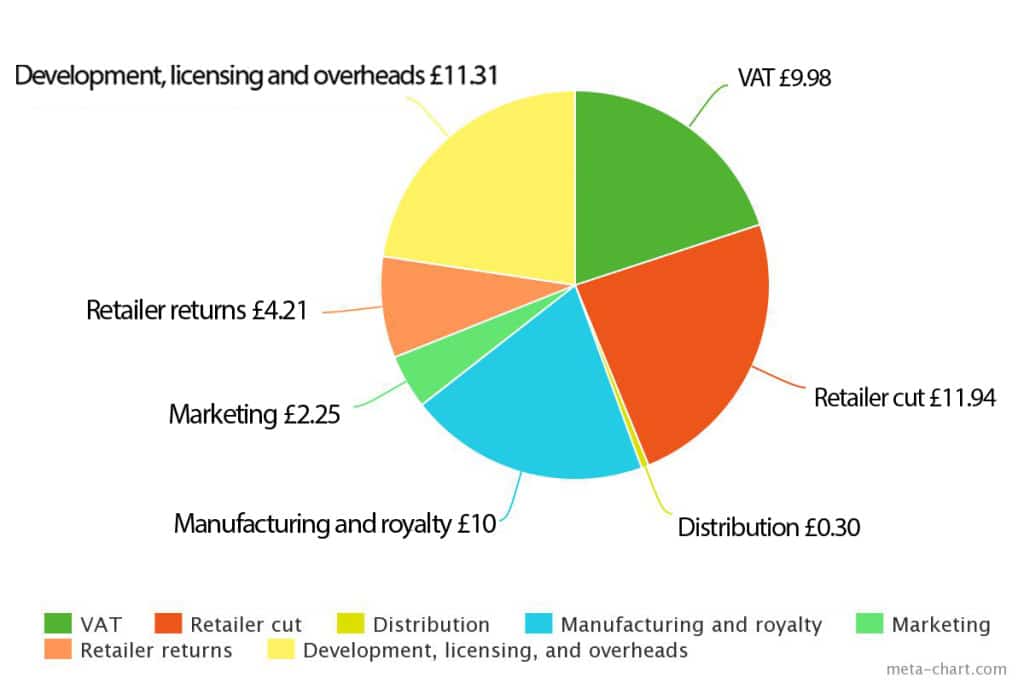

Here is another visualisation of the breakdown of a £49.99 retail game, from a source close to UK retail, who preferred to remain anonymous:

So, yes, very different. Truth is, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question, with so many different retailers, publishers, and methods of distribution.

But how important IS retail, really? Aren’t most games sold digitally now?

This is an extremely pertinent question - and another one that’s really hard to answer because people will not let go of their data. The current video game charts, for instance, consist entirely of physical sales and are basically bullshit. Chris Dring, who edits UK trade publication MCV (which has been campaigning for months to get proper digital sales data out in the open), gave me an informed estimate.

“This is very hard to accurately quantify. According to IHS, digital console and PC games (this includes free-to-play and DLC, but excludes mobile) accounted for about £1,048bn last year. That, unfortunately, is just an estimate because there is no digital data available. The boxed games – based on GfK Chart-Track numbers – was £915m. So the split is about 54 per cent in favour of digital – but these are just estimates.”

That’s the total games market, though. When you look at particular games, the split can be very different. “A lot of games are released digitally-only now, to circumvent the high costs of physical distribution,” Dring points out. “[But] if you are talking specifically about big games that are released digitally AND physically, the vast majority of sales are still made in shops. Earlier this year, we combined SuperData figures with Chart-Track numbers, to discover that Battlefield: Hardline sales were 82% physical and 18% digital during its first month – and that was pretty common across the whole spectrum. Between 75 – 80% of sales of big boxed games appear to be made on the High Street over digital distribution. But this is extremely rough numbers.”

So, yeah. 80% of sales of the biggest games are still made in shops. Retail is very important.

Wouldn’t we all save a lot of money and generally be happier without retail, though?

You might think, based on all of this, that we’d be better off if retail wasn’t a part of the picture. Games would be cheaper. Publishers and developers would get a larger cut of the price. We could all live in a Valve-esque post-retail world where the games are plentiful and cheap. But realistically, retail remains vital to the games industry, in the UK and elsewhere.

Specialist shops like GAME in the UK have been really important, historically, in championing games on the high street and growing the gaming audience. Without retail, games wouldn’t be nearly as big as they are, which would mean development costs couldn’t get nearly so high, and certainly nobody would be able to afford to make something like Destiny. Game shops also help to educate less informed buyers: people who've only bought a couple of games before, or who are buying gifts.

For publishers, game shops are also a very effective marketing tool. “Games specialists like GAME also have millions of customers, which are people that publishers will want to reach,” says Dring. “As a result, these savvy retailers are becoming effectively marketing vehicles. They are putting on events so that gamers can go into their local store and play the latest Assassin’s Creed or whatnot. The games industry doesn’t have music venues or cinemas for fans to go and experience their hobby, the games store is the closest we have. I would expect as more games are released digitally, these stores will be less about selling games, and more about playing them.”

So, who sets the prices for games in the UK? Why are things sometimes so much more expensive for us?

It’s mega annoying when you look at a game or, commonly, a piece of DLC and see that it’s $19.99 in the US and £19.99 in the UK. WTF? How is that justifiable?

We get a lot of questions about this on Twitter and often, people’s instinct is to blame the publisher or the developer. It’s easy to throw around accusations of gouging. In reality it’s mostly retail that sets the prices, though publishers obviously recommend prices (that’s the RRP), and that differs by country. I spoke to Jas Purewal, a lawyer who specialises in the gaming industry, about exactly how this works.

“There are no laws concerning what the minimum cost has got to be. In fact, the position in the UK and now across the EU is just the opposite,” he told me. “There are laws which give the retailers a latitude about what price point they can sell at. It’s what’s called the ban on price maintenance, or retail price maintenance. And so a publisher can set what they believe the recommended price could be but they can’t force the retailer’s hand.”

This wasn’t always the case - publishers used to be able to say “you can’t go below this price”. Publishers and retailers could also collaborate to make sure that nobody sold it for less than a certain amount, which is price-fixing. Nintendo actually got done for this in the mid-’00s, and had to pay a hefty fine.

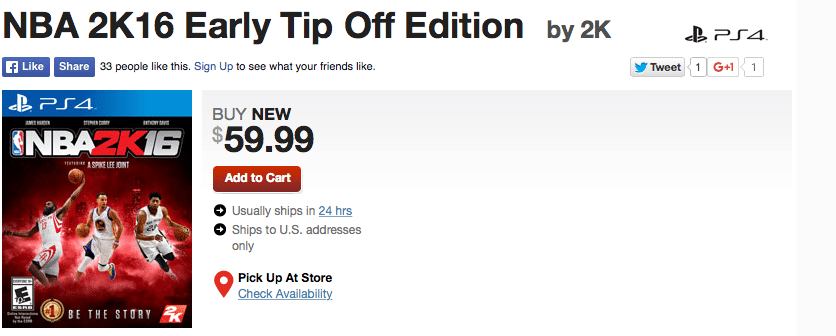

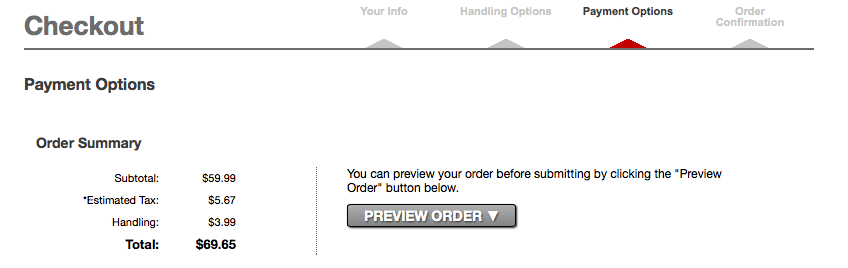

It seems, from my research, that regional discrepancies are largely down to a) how retail works in that particular country, and b) what the publisher believes to be a fair price in that country. Another thing to keep in mind here is tax. In the UK, we pay 20% VAT on games. In America it varies by state, but is usually much less - and it’s also not included on the sticker price, it’s added at purchase. So a game might look like it’s $60, but when you actually buy it, it’s closer to $70. Here’s an illustration of that discrepancy, via Gamestop's site:

So, divide a UK price by 1.2 to account for 20% VAT, and you’ve got a fair comparison with the stated US price. It closes the gap between UK and US pricing, though of course it doesn’t amount to all of it.

Here’s a case study. I raised my eyebrow at the price of Rock Band 4 in the UK - and, to its credit, publisher MadCatz responded by explaining exactly what was going on with the pricing: Rock Band 4 is £219.99 in the UK and $249.99 in the US, which is closer to £160. Calculate the UK price before tax, and you’ve got about £183, which is the equivalent. Suddenly it’s not that much of a difference. Consider that the cost of doing business in the UK - like shop-front rental, distribution, and wages - is also higher, and the differences aren’t so massive.

DLC, though? There's no particularly great reason why there should be an enormous discrepancy there, but bear in mind that the amount of tax a company might pay on its profits in the UK or EU as opposed to elsewhere might be higher.

It's All Fucked Shirt $22.14 |

|

It's All Fucked Shirt $22.14 |